One of New Zealand’s earliest farms, Mana Island is now a scientific reserve. Denise Stephens learns about the restoration projects.

Gannets basked in the sun, their cries filling the air. From where we stood at the top of the cliff, the colony looked real enough, but the birds were concrete models and the sounds were recorded. It’s part of a programme to attract gannets to breed on Mana Island. Our guide, Laurie, clambered down to see if there were any real gannets. One male had been spotted recently, but he wasn’t in residence that day.

On a guided walk around the island, we learned about the revegetation work, and saw the birdlife that has flourished as a result. Volunteers from Friends of Mana Island (FOMI) have helped with replanting and pest control for over 20 years. Now they run regular day trips to the island.

We assembled at Mana Marina, in Porirua Harbour, well before departure time so that Laurie and our other guide, Linda, could lead us through a biosecurity check on our bags and shoes. We wiped the soles of our shoes on brushes and disinfecting pads as a final precaution before boarding the Charmaine Karol. The boat eased along the harbour, past early morning rowers, kayakers and waka ama paddlers reflected in the calm waters.

Once out of the harbour, the skipper revved up the boat. Twenty minutes after we left the mainland, the Charmaine Karol nosed onto the shore at Mana Island. We disembarked down a steep gangplank, then walked up the similarly steep pebble beach.

Farming History

The tour started at the old woolshed, a red wooden building built in 1887. Wool was exported from the island in the 1830s and farming continued until the 1980s. When scrapie was discovered in 1976, all the sheep had to be killed, and cattle farming lasted only a few more years. Farming changed the environment as native vegetation was removed to make way for pasture, and pests were introduced. Mice were a particular problem – when the woolshed door was opened, mice would scurry all over the floor.

The Department of Conservation took over management of the island in 1987, and since then has worked with FOMI on revegetation and eradicating pests. Linda and Laurie told us about this work as we walked along the Tirohanga track, which loops around the island.

Revegetation

The first plantings were in the valleys, to link up with the small remaining area of original forest, mainly kānuka and mānuka. We learned how to tell the difference between these: mānuka is slightly prickly due to its seeds, whereas kānuka is not. “Kind kānuka, mean mānuka,” as Linda helpfully described them.

Seeds were collected from the island’s four surviving milk trees (Streblus banksii), to propagate more trees. Our guides pointed out some of these along the track – male and female trees are planted near each other to enable pollination.

The views from this side of the island looked out over the bush towards suburbia, from Plimmerton around to Tītahi Bay. In the 19th century, on the foreshore below us, whalers once boiled down whales for blubber. The island offered an excellent vantage point for whale-spotting.

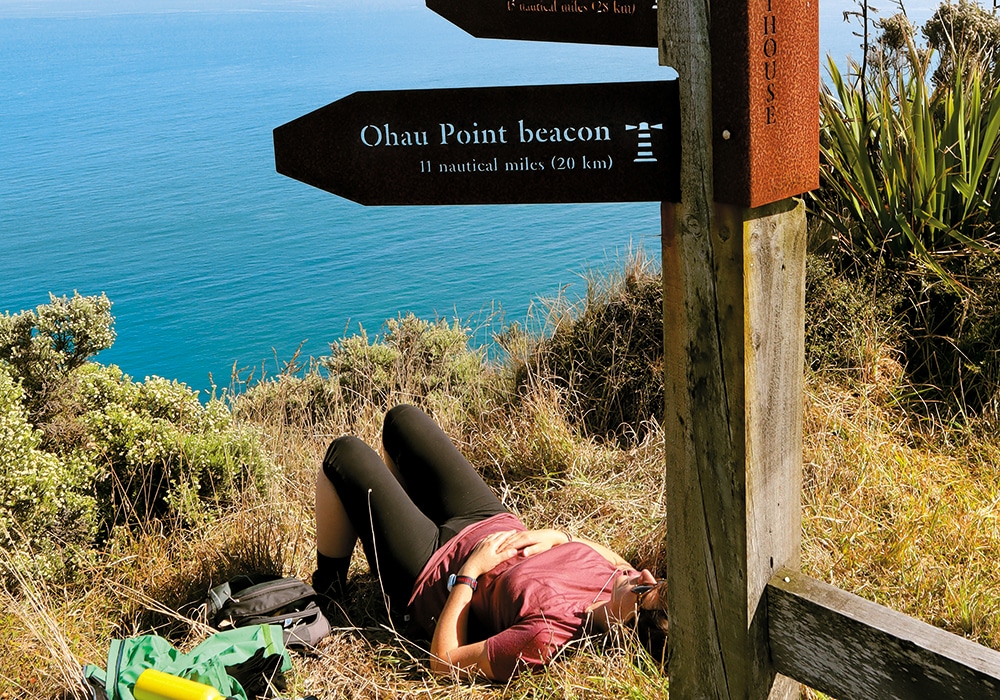

The track was well formed, but became steeper as we headed up the hill. It needed a reasonable standard of fitness and a few rest breaks here and there, but everyone in the group, from pre-teens to seniors, made it to the top.

Wildlife

Along the way, we looked out for birdlife. The takahē proved elusive, although two people at the front thought they saw them. Laurie gave us a lesson in how to identify takahē poo – it’s large, long, and green from the grass in their diet. Fresher droppings are very green, while older ones are bleached pale by the elements. Equipped with this knowledge, we could see recent signs of the takahē as we walked up the track.

Mana is home to other rare bird species, such as the fernbird. Their distinctive “tut tut” call was a signal to look for them flitting through the bush.

Gecko viewing spots are scattered along the track, with a plastic flap covering a warm hiding place that encourages them to gather there. When we lifted the flaps, some Duvaucel’s geckos just lay there, while others scuttled away.

Lunch at the lighthouse

Finally the track levelled out at the top of the island. After looking at the gannet project, we headed to the old lighthouse site for a lunch break. The only remains of the lighthouse are brick foundations and the keeper’s garden, surrounded by a ditch to keep livestock out.

The lighthouse was moved to Cape Egmont in 1881 because its beam was too easily confused with Pencarrow lighthouse.

We unpacked our lunches at a picnic table made from timber recycled from the old wharf, which was demolished to discourage casual visitors. Over lunch we rested our legs and took in the view. Kāpiti Island was clearly visible, while Taranaki was a faint mark on the northern horizon. In the other direction, the South Island was a hazy outline.

After lunch we split into smaller groups, so that the wildlife would be less disturbed by our presence. Our newly acquired knowledge helped us spot fernbirds, bellbirds, kākāriki and harrier hawks. We stood still watching geckos darting through the grass at the edge of the track. This side of the island seemed more peaceful and remote from the outside world. Here it was obvious the efforts to restore vegetation have created a haven for wildlife.

Eventually we arrived down at the shore, where a carved pou looks towards the mainland. Māori first settled on Mana around 1400, and the Ngāti Toa leader, Te Rauparaha, built a whare and kūmara gardens along the beach area. Today the only human inhabitants are DOC staff who live nearby.

We walked along the beach to wait for the boat, carefully avoiding a flock of shags. A lone gannet wheeled overhead before heading out of sight towards the calls of the fake birds.

More information

Friends of Mana Island run regular weekend guided tours. Cost: $60 for adults, $30 for children under 14. Find out more at manaisland.org.nz/visitors

Motorhome parking is available close to Mana Marina at Ngāti Toa Domain, and at the Plimmerton NZMCA Park.