Alongside the track, the trees were uncannily still as if something momentous were about to happen.

I listened to my own footfalls and then, from up in the canopy, came a faint sound—tssst tssst zir zir—and a tiny shadow flitted past like a spirit. I leant against an old tree trunk and lifted my binoculars. There it was.

Its white head gave it away as it busily searched for food, inspecting each leaf and twig from all angles and prying nosily into cracks and crevasses. White-head are one of the many species of our avifauna that have been brought back from the brink by the dedicated efforts of thousands of workers and volunteers.

New Zealand is a divided nation. Wire fences march across steep hills and dissect agricultural flatlands like cross-stitch on a blanket. And in the 1990s, with number-eight-wire ingenuity, the idea began to evolve of using specially adapted fences to create mainland ‘island’ sanctuaries that could help conserve our dwindling wildlife by banishing the pests that hold it under siege.

The concept heralded a shift in conservation from being species-centred to the protection of whole eco-systems.

Now, New Zealand leads the world with its critter-proof fencing, and it has become one of the most powerful weapons in the War of the Rodents. Saying it’s not been an easy exercise is understating the obvious.

The athletic prowess of our various pests is remarkable: possums can leap as high as 1.2 metres, rats climb up 70 centimetres of metal and stoats one metre, mice squeeze through tiny gaps and rabbits dig deep. The security fences developed to repel all these invasion abilities are amazing in their detail and have taken years of research and fundraising.

I became curious, then fascinated, then fixated by the concept of fenced sanctuaries and decided to visit as many ‘islands’ as I could.

The quest started small. The first tick was to one of the few invertebrate sanctuaries in the world. Outside Cromwell, an unprepossessing area of long grass is sectioned off to preserve the Cromwell chafer beetle whose existence is threatened by land use and the imported red-back spider. Years ago, I went to another invertebrate asylum in the Far North at Te Paki where fences protect New Zealand’s mammoth-sized snails.

I’m unlikely to get onto Maud or Stephens Island to see the enclosures for native frogs but I did visit the equally unconventional Mokomoko Dryland Sanctuary in Otago, where a jumble of rocks has been cordoned off to protect two species of New Zealand skink from marauding mice. It has been a successful experiment and when I peered through the fence, I spotted two of these endearing little reptiles basking in the sun.

Although such innovations are interesting, visiting them is not intriguing for most wandering motorhomers, but there are many others that are. The largest and most dramatic is Mt Maungatautari (Sanctuary Mountain), the home of my white-head. Encircling this volcanic massif, which rises gently from Waikato dairy land, is a 47-kilometre-long barrier enclosing 3400 hectares of stunning podocarp forest.

This impressive engineering feat has a coved lower edge so that digging invaders are thwarted, and is topped with a guttered, steel canopy to foil of attempts of vaulting trespassers.

An electronic surveillance system operates 24/7 and if there is a breach, an alarm sends a warning to a monitoring officer. Pathways wind through mosses and ferns under a dense canopy of sky-reaching trees that have stood there for centuries. No longer besieged by predators, a variety of avian natives have found safe haven.

Further south is a small and thriving wildlife crèche, refuge, and education centre at Rotokare in Taranaki. Wetlands and forest are set around a gently riffling, reed-fringed lake. Although the overall theme is restoration and conservation, recreational boaties can still take to the water as they always have.

Birds were re-introduced into the area cleared of unwanted invaders. Every last mouse had apparently been removed. I am not sure how that’s calculated but if it’s true, it’s commendable. It’s hard enough to get rid of them from my kitchen cupboard.

The walk around the lake takes about an hour and a half. I only did part of it but was rewarded with the sight of a handsome saddleback just a body length away from where I was standing. Its bright red wattles waggled as it energetically grubbed for its lunch.

Another cause for celebration is Bushy Park on the west coast of the North Island near Whanganui. This 245-hectare sanctuary comprises wetlands and a fine remnant of lowland rainforest.

All the stoats, ferrets, weasels, possums, feral cats, hedgehogs, and rats have been dispatched to their various heavens and a 4.8-kilometre, pest-proof fence ensures their relatives remain in exile. A forest walk brings avian surprises.

Some, such as stitchbird, saddleback, and black robin are back from the brink. It would be hard to miss the huge northern rata, Ratanui, reported to be the largest in the world and possibly 1000-or-so years old.

Further south near Dunedin is the Orokonui Ecosanctuary. On a misty day, the regenerating bush was reminiscent of a Gondwanaland cloud forest and a glimpse of what the South Island was like before humans arrived. Birds, heard but not seen, whispered and whistled among the ghostly branches.

This 307-hectare of kanuka and three- to five hundred-year-old podocarp forest is fenced off on a hill above the Otago Harbour. Protecting it has taken many years of hard labour but in the end, it is a triumph.

There are two sanctuaries that are singular in that they exist at all because both are in desirable real-estate territory in expanding cities.

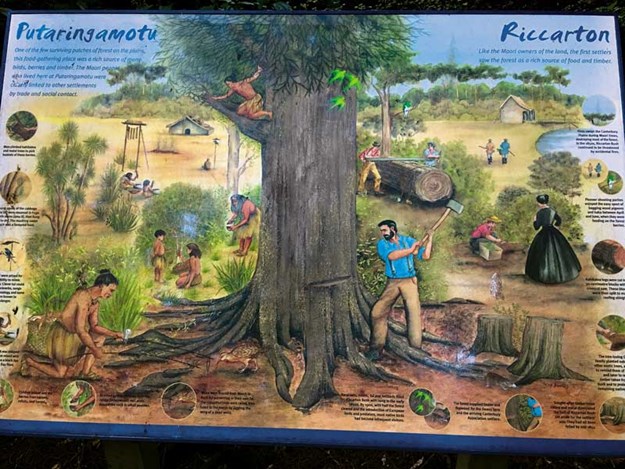

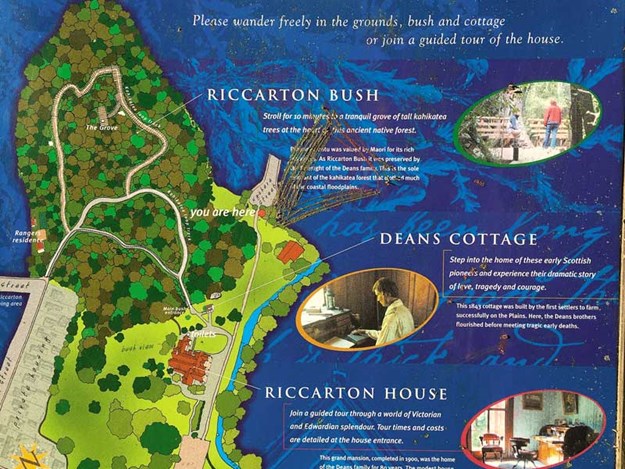

The first, Deans (aka Riccarton) Bush, was a find—the last remnant of the podocarp kahikatea forests that once blanketed Canterbury’s flatlands slap bang in the middle of Christchurch. Two ill-fated pastoral pioneers, John and William Deans, came here in the 1880s. They named their farm Riccarton.

A few years later, William drowned. And then, John succumbed to TB, but not before he’d made sure the bush on their property would be preserved forever. The fenced 12 hectares of forest is next to their lavish homestead, Riccarton House, and pathways lead through groves of towering kahikatea that are 600 years old.

The fact that this lovely spot has survived a developers’ zeal is remarkable. It is a refuge for many native birds and a crèche for young kiwi before they are returned to the wild.

The second is Zealandia in Karori Valley, which is perhaps the best-known of the country’s fenced sanctuaries. It was once Wellington’s water source and is centred on an old reservoir. In the first stages of pest eradication, three tonnes of deceased possums were removed. Mice still give administrators the run around.

Nonetheless, 40 species of native bird have been recorded in the valley and there is a sizeable number of tuatara, geckos, weta, and frogs. A drab little North Island robin bounced over to where I was sitting and peered inquisitively at my shoe. Nothing from the Beehive could have given me the same sort of buzz.

The creation of these refuges has taken foresight, planning, ingenuity, deep pockets, time, and a lot of worn boot leather. It could not have been done without a vast volunteer army, a force made up of thousands of dedicated individuals who do battle and ensure these islands, which are now quoted around the world as beacons of hope, are successful.

Among them are many RV owners who, by making the most of our extraordinary environment, have good reason to support its preservation and that of the creatures that also call it home.