The road to Karamea over the Radiant Range is, at times, nothing but a narrow ledge snaking over rearing hills swathed in rainforest. It’s not for queasy stomachs.

I felt a frisson of relief as we finally dropped to the swampy coast and its lumpy pastures bristling with nikau palms to arrive eventually at the end of the road and the beginning of a whole new world.

Most people equate this part of New Zealand with wild stretches of beach and the start (or end) of one of New Zealand’s Great Walks—the Heaphy Track. But you don’t have to haul on tramping boots and hump a pack to experience the natural world that makes up one of the country’s most astonishing regions.

Lake Hanlon

Fifteen kilometres before Karamea township, a sign indicates the walk to Lake Hanlon. It’s easy to miss but try not to. After the long and tortuous drive from Westport, 20 minutes of leg-reviving walk through low forest led to this serene lagoon of black-coffee water.

The tangle of forest that hugs its banks was mirrored in its surface. No breeze disturbed the motionless water but one small ripple radiated out from the touch of a dragonfly. The only other movement, apart from our own, was a small tree branch falling to the ground. In so profound a silence, it sounded like a pistol crack.

An interesting fact about Lake Hanlon is that it’s very new. It was formed in 1929 as a result of the earth-altering convulsions of the Murchison earthquake. Hot though I was, I doubt I’d ever swim there. Its dark waters look as if they might harbour taniwha or hungry eels.

Oparara Basin

If you miss Lake Hanlon, there is another, rather swampy, mirror lake just off the Moria Gate/Mirror Tarn Loop track in the spectacular Oparara Basin. The basin is honeycombed with caves, tunnels, and archways but the Gate of Moria, where Tolkien’s Gollum might well still be hiding, is perhaps the best known.

The four-kilometre loop-walk to the lake and cave led me through a fairyland rainforest where delicate mosses, ferns, and epiphytes clung to massive trees trunks. It took about one-and-a-half hours. The last rocky descent to the arch taxed my climbing skills but not as much as it did on the way back up.

The gate was a sight to behold—a great arc of rock shaped like an amphitheatre and open to the tea-brown river. The ceiling dripped with short, slow-growing stalactites. Hanging roots and vines festooned its roofline.

The most famous caves, and the most difficult to get to (a guide is required), are at Honeycomb Hill, and they harbour the largest and most varied collection of fossil birds in NewZealand. That sounded interesting. Around 50 species are recorded include several moa. Maybe I’ll tackle those walks next time.

Getting to the Oparara Valley can be awkward. It’s along an old logging road that is narrow, steep, and unsealed. It’s not for the faint-hearted and definitely not for motorhomes. But if you can cadge a lift or organise one through the i-Site in Karamea, it’s a spectacular drive through a karst landscape mantled in primeval rainforest.

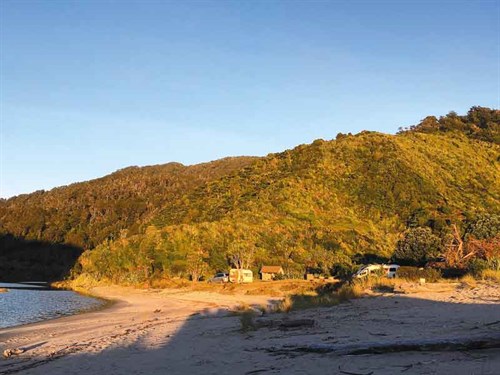

Kohaihai

It’s an easy drive from Karamea to the end of the road at the Kohaihai shelter. The DOC site there, among flaxes and forest and between the Kohaihai River and the sea-battered beach, is one of the great, wild RV camping spots in Aoteoroa. We stayed for three days, as there are several tracks that are wonderful to explore.

On our first evening at the camp, and feeling lazy after our excursion to the Oparara, we took on the Zigzag Track. It leads up a hill behind the camp and from the name, its nature is not hard to imagine. The climb was steady but not too challenging. Instead, it was the view from the summit that took my breath away.

The great coastal vista unfolded before us—the unruly forests, the exclamation marks of the nikau palms, the untrammelled beaches, and the dark sluggish river. A retiring sun painted bold red streaks across the horizon and the sea hissed against the sand like heavy breathing.

Next morning, we set out across the bridge on the Nikau Walk, which only took us a dawdling hour or so. Nikau palms clustered in social gatherings. Their great plumed heads nodded in the stiff wind setting up a murmur that sounded like malicious gossip.

Scotts beach

I’d love to know who Scott was but have so far drawn a blank. Whatever the answer, it makes no difference to this popular walk along the first part of the Karamea end of the Heaphy Track. On the other side of the Kohaihai bridge, it zigzags uphill through more nikau groves and dense rainforest. After we’d walked for about 35 minutes, the summit gave us great views of the coast.

We walked on through the immense trees. Forests like these (all too rare), where the forces of nature are undiminished, have a palpable dignity. Its presence closed in around us as if we were entering a cathedral.At Scotts Beach, lofty cliffs and rainforest hug a lovely sandy stretch and, except in the high season, you may, like us, have the place to yourself. The blue-grey sea looked friendly, and after a hot walk, it beckoned like a siren.

But even at its most benign, it hides currents, rips, and treacherous undertows and there were warnings not to swim. Myriad sandflies were far less dangerous and far too friendly. We’d forgotten the insect repellent.

Karamea estuary

Back in Karamea, a short walk gave us a good overview of how this far-flung township came into being. The track borders the estuary and the north bank of the Karamea River. It’s an easy stroll and the whole loop takes an hour.

Heading towards the West Coast? Read more MCD articles on things to do and see in the region.