History books often contain stories to rival a top fiction novel; Paul Owen unearths a particularly fascinating story of luck and foolishness from yesteryear.

Imagine for a moment that you are one of four threadbare prospectors looking for gold, high on a windswept plateau southwest of Reefton at the beginning of the 20th Century. You’ve been poking your pickaxe into promising places up there for more than a month, more or less living off the land. You stop for a late lunch at 3pm on November 9, 1905, which happens to be the birthday of King Edward VII. As you drop your pickaxe it makes a telltale sound as it chips the ground near your feet.

There’s evidently solid quartz beneath the concealing layer of moss. You and your three mates – Billy Meets, Davy Ross, and Ernie Bannon – quickly scrape back the moss, and there it is – a rich vein of lustrous gold held captive in the tight embrace of the pink and white rock. Such was the luck of Australian-born Jimmy Martin on the King’s birthday at Waiuta 117 years ago. The quartet had just discovered one of the richest gold-bearing quartz reefs ever found, a strike that would eventually see 750,000 ounces of the precious metal extracted from the site.

At today’s gold prices, that yield would be worth more than $1.7 billion. Not that the quartet of gold-seekers would fully enjoy the riches of their find. Having already staked their claim on that piece of land, they quickly decamped to the nearest pub and toasted the King’s health and their good luck. The celebration quickly attracted the attention of one P. N. Kingfield, a visitor to the West Coast from Auckland, who instantly offered the men 500 pounds each for the claim. They eagerly accepted his offer and over the next six months, Kingfield would stake further claims on neighbouring land to ensure that a large company would be interested in buying the rights to work the reef from him. The British-owned Consolidated Goldfields (NZ) Ltd, already an active participant in the mining industry around Reefton, snapped up the rights for 30,000 pounds. In that moment, the Blackwater mine came into existence and the attendant town of Waiuta was born.

Turning into a town

Before the work of extracting the gold could begin, accommodation for the miners and their managers had to be built. By 1908, the company had built rows of single men’s huts, several multi-roomed houses for families and a boarding house for visitors. The town’s layout had already been surveyed, and the network of streets was being extended. As time went on, Waiuta began to look more like a proper town rather than a temporary camp. Although the vein of gold was narrow, it continued to extend far into the depths of the earth. Eventually the miners would follow the descent of the reef to 900 metres below the ground, the final 300m being lower than sea level.

More than 1.5 million tons of quartz would be brought above ground then sent down a steep tramway to the Snowy Battery to be stamped and crushed, with any residual quartz dust washed with cyanide so that further gold could be extracted from it. The ongoing presence of gold in the reef so sustained mining operations that the miners soon eschewed renting houses from the company and began to build their own. Entrepreneurs began to set up shops to service the town and a school and a post office were established. The local union used the registration fees of miners to provide free health care for all its members and set up a union-financed maternity hospital in the town. The miners were now frequently getting married and raising families at Waiuta, secure in the knowledge that the reef continued to yield. A rugby field was developed and Waiuta became one of the most feared league teams on the coast. In the 1930s, a swimming pool of Olympic standard was dug out and set with concrete. Waiutans proudly boasted that it was “the best pool on the Coast”.

In true mining tradition

The Empire Hotel was possibly the hub of the Waiuta community in true West Coast mining town tradition. In 1919, a Board of Trade report identified that the mining communities of the West Coast consumed twice as much alcohol as elsewhere. The war hero editor of the socialist-leaning Māoriland Worker, Ettie Rout, felt that this was mostly due to the harsh working and living environment of underground miners.

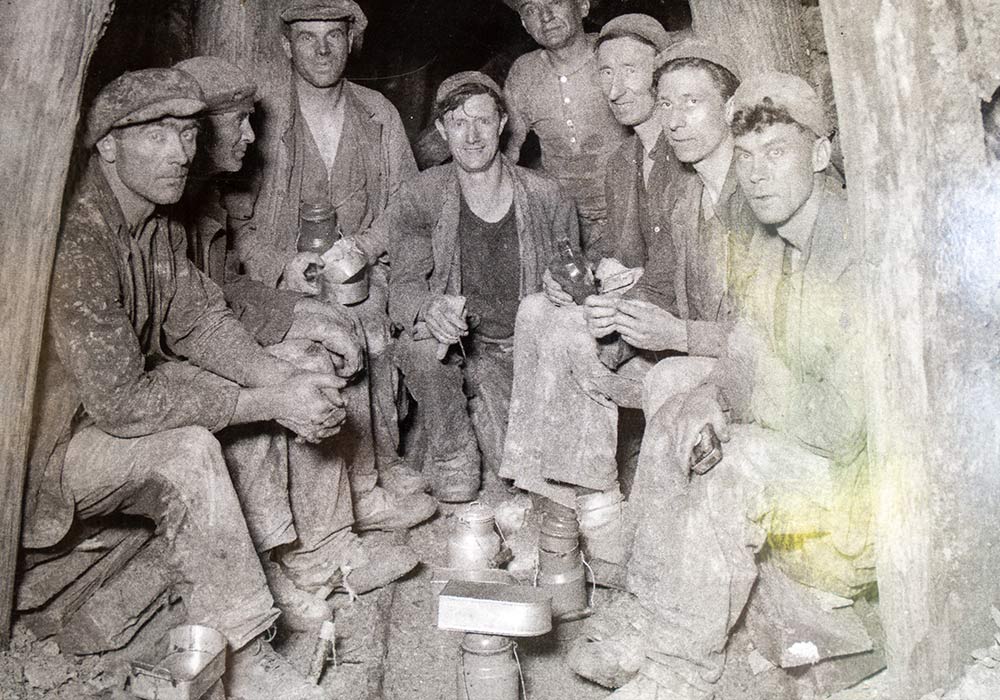

“They live in gloomy valleys, they work in holes in the earth, they live on the West Coast where it is nearly always raining, where 80% of the men drink, drink, drink, in a wild endeavour to forget who they are and where they live.” Rout’s bleak observation is somewhat at odds with the more than 200 photographs that long-term Waiuta resident, Joseph Divis, took during his time working at the Blackwater mine. They paint a far happier picture of life there. Born in the Czech Republic and trained as a miner in Germany where he first developed an interest in photography, Divis arrived in New Zealand in 1909, moving to Waiuta in 1912. Most of the surviving photographs taken by him depict the town in the 1920s and 1930s, when the population was at its peak of more than 600 residents. Divis often used a timer on his camera’s shutter so that he could also be seen in the photographs. They often show a satisfied man in his trademark safari suit, enjoying some big event such as the town’s 25th anniversary.

In 1936, Divis sought and was granted New Zealand citizenship. A comment on his application reveals some of the pride he felt as a member of the Blackwater mine community. To him it was probably a socialist utopia given the free health care and the way workers were able to share some of the profits of the mine.

“I own my own house at Waiuta, it is a four-roomed wooden cottage. I am a shareholder in a gold-mining enterprise on the West Coast and am in comfortable circumstances financially.”

Unfortunately, the photographic records provided by Divis of Waiuta life came to a sudden halt. In March 1939, he suffered a serious head injury while working in the mine and endured a long period of partial recovery at Reefton Hospital and a sanatorium at Hanmer Springs. While still at the latter he was suddenly interned as an enemy alien in 1940 and transferred to the prison on Soames Island in Wellington Harbour. This happened despite his citizenship, lack of internment during the First World War, and the fact that he was still suffering from brain trauma sustained in the mine accident.

Divis was released in 1943 and quickly returned to Waiuta, where he continued to work in the Blackwater mine, apparently on light duties. When the mine closed in 1951, and the town was virtually dismantled within the next three months, Divis stayed on, acting as a postmaster for former residents of the town and sending their correspondence on to their new addresses. When signing off a letter in 1957, he called himself ‘Joseph Divis, telephonist of this Mystic Ghost Town’.

The latter is an accurate description of Waiuta today. Divis would live a further four years there before his burial in Reefton cemetery, and his house is one of the few remaining structures that is relatively intact. Others include the maternity hospital, which has now been restored and converted into a tramping lodge, complete with a dining area that includes the solid Rimu vestibule of Waiuta’s former Anglican church. There’s also the barber’s shop run by proprietor, Ray Bartlett, and few other dwellings left to finally decay by lingering Waiuta residents other than Divis.

More impressive are the ruins of the above-ground infrastructure of the mine, including the communal bathhouse where the miners cleaned up after a day underground and the winding engine of the 574m-deep Blackwater shaft, which was replaced in 1943 as the point of entry and exit to and from the mine by the 900m-deep Prohibition shaft. The Blackwater shaft was then used as ventilation for the large underground pumps that constantly sucked groundwater out of the mine so that operations could continue. When the Blackwater shaft collapsed in 1951, the pumps could no longer operate causing the water levels to rapidly rise, and the mine had to close. It must have been galling for the miners to think of all the gold that remained almost a kilometre below ground, and how it would have continued to sustain their lives at Waiuta.

The former post office might have lost its walls but is now enjoying a second life as an information centre. It points the way to the many tramping tracks that use it as a starting point. There’s the 90-minute town walk from there plus the 15-minute hop to the dried-up swimming pool and back. The Prohibition mine, the deepest shaft in the location, is 2.2km away and you get to enjoy extensive views over the Reefton area on the way. The return track down to the Snowy Battery and back up again takes 2.5 hours to complete and is worth the effort for the glimpse it affords of early 20th Century gold mining technology, especially the colossal cyanide tanks. Adventurous trampers can also walk the three-hour journey to Big River past many more mining relics including the St. George Mine and Big River South Mine. The route is also a great ride on a mountain bike.

You’ll need to book first if seeking to stay the night at Big River Hut. The hut is a great starting point to walk the 7km one-way track to the Golden Lead Battery. It’s an easy-going climb at first over an old bush tramway, but the final bit of the climb up to the battery is more challenging, and the descent will be a test of the knee joints.

Even if you’re not a walker or a biker, Waiuta is still well worth a visit. Simply turn off SH7 some 20km south of Reefton and drive up the 17km climb over a well-maintained gravel road fringed by native bush. You’ll emerge from the trees onto a grassy plateau near the site of the former Empire Hotel. Your ‘mystical ghost town’ exploration has begun.