Viv Haldane finds out more about a family connection to the world’s only surviving steam-powered Fell engine in a Featherston museum.

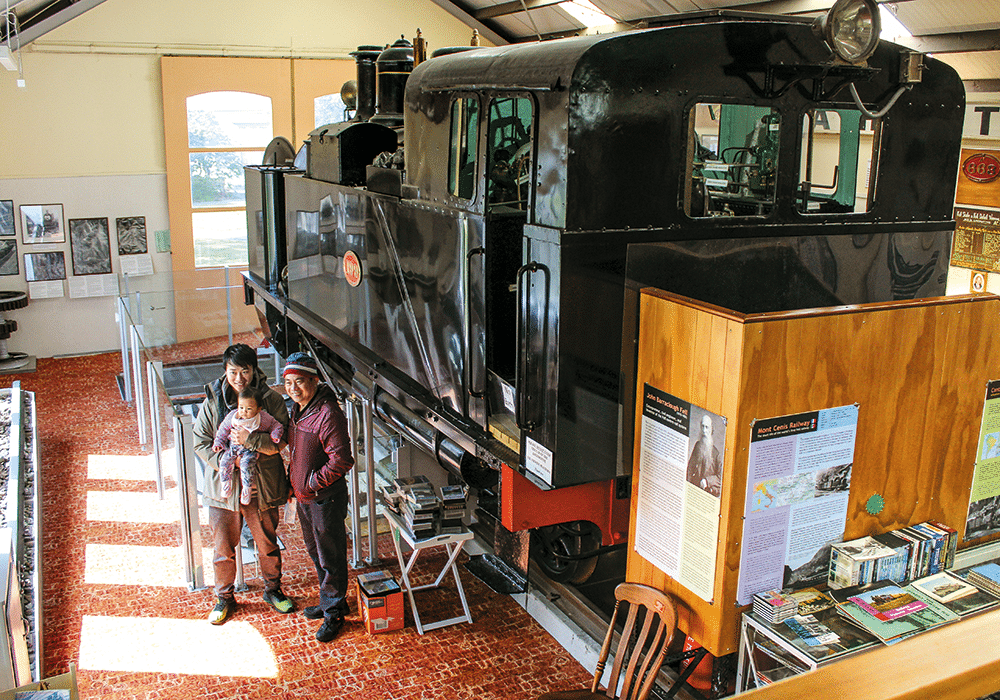

The town of Featherston, northeast of Wellington, is an hour’s drive from the city over the twisting Remutaka Hill road. Usually, we head straight back home to Hawke’s Bay from here, but this time, my partner Glenn and I decided we’d have a break and visit Featherston’s Fell Locomotive Museum.

The railway museum is a place I’d heard my mother talk about, because her cousin Noel Meek had been involved with it for many years. I wasn’t exactly sure how, so this was an excellent time to find out. The museum’s location just off the main road through town, on a side street and with clear signage, makes it easy to spot.

When we arrived, a helpful volunteer, John Munro, gave us a detailed commentary about the history of the Fell locomotives and the community they serviced. His knowledge was impressive, and I assumed he must be an avid trainspotter, but this wasn’t so. He’d become involved by chance while out walking when he got chatting to a woman who happened to be the museum’s president. John mentioned he lived near the museum and bada bing! Before he knew it, he’d agreed to work as a volunteer. John’s positive response to a stranger’s request is typical of the community effort that keeps museums like this going.

The Fell locomotive

Wairarapa was a thriving farming region in the 1800s, but the Remutaka Range created a barrier to the south. Although there was a road across this steep terrain, the journey to Wellington was arduous. When the railway line between Upper Hutt and Featherston opened in 1878, a solution for transporting goods and passengers came in the form of a locomotive designed by John Barraclough Fell, an English engineer.

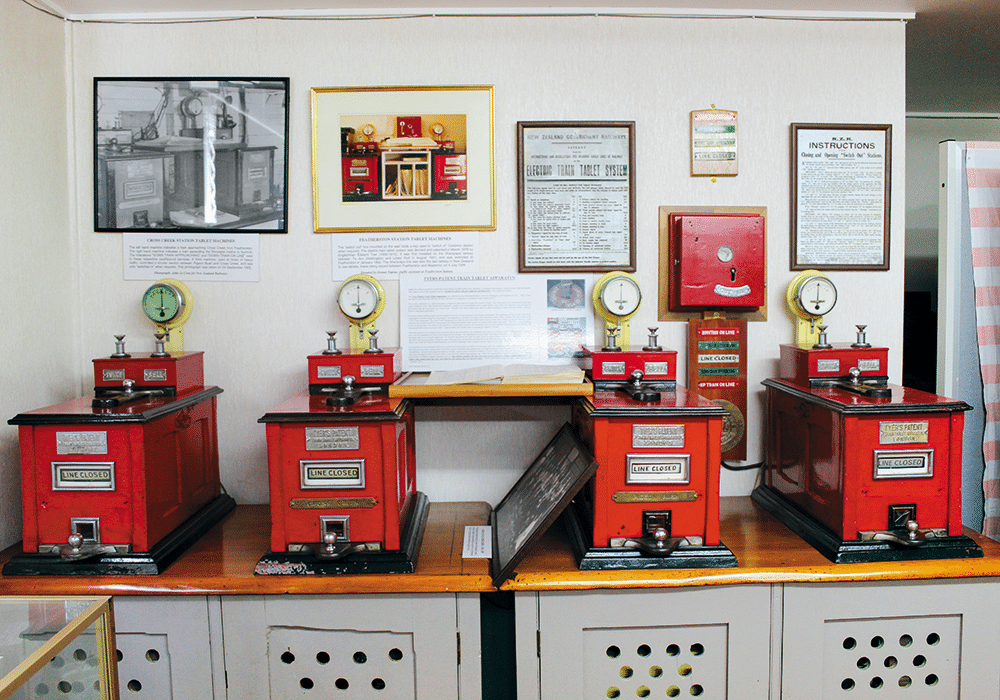

Six Fell engines connected Wellington and Wairarapa. “It was only a 4.8-kilometre gap, but it was too steep for regular trains, so for 77 years, trains would come from Wellington loaded up, then once they reached the summit, they went to a marshalling yard,” John told me. “Their wagons would be unclipped, and the Fell locomotives would take them 4.8-kilometres to a marshalling yard called Cross Creek. The ascent took 45-50 minutes, depending on weather conditions. Just outside Featherston, they’d unclip again, and the wagons would carry on to Wairarapa and Hawke’s Bay, hooked onto a regular train.”

The secret to hauling up the steep mountain railway was a centre rail. The Fell trains had four horizontal grip wheels under the boiler, which would clamp onto the centre rail for added traction when climbing the incline. Brake blocks, fitted to the locomotives and vans, pressed against the centre rail when descending. “The design was Victorian heavy engineering at its best. Built during the 1880s, it was a very manual operation. The trains carried a mix of produce, with some of it going to Wellington Harbour for shipping overseas, as well as passengers,” says John.

A restoration project

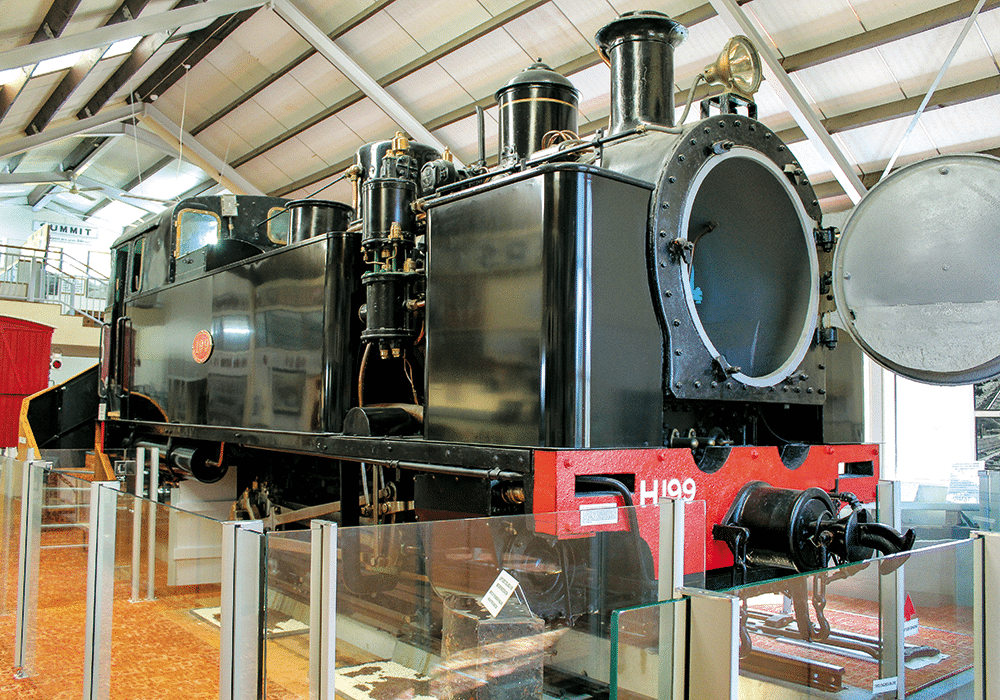

When the Remutaka train tunnel opened in 1955, the Fell engines were no longer required. Five of the engines were scrapped in 1957, but fortunately, H199 was spared and gifted to the town of Featherston in 1958. The brake van, F210, was acquired from NZ Railways by Auckland’s Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT) in 1968.

The Fell locomotive sat in a children’s playground in Featherston from 1958 until 1981 when Friends of the Fell Society began work on it. In 1984, H199 was moved to the purpose-built locomotive museum where it was completely rebuilt.

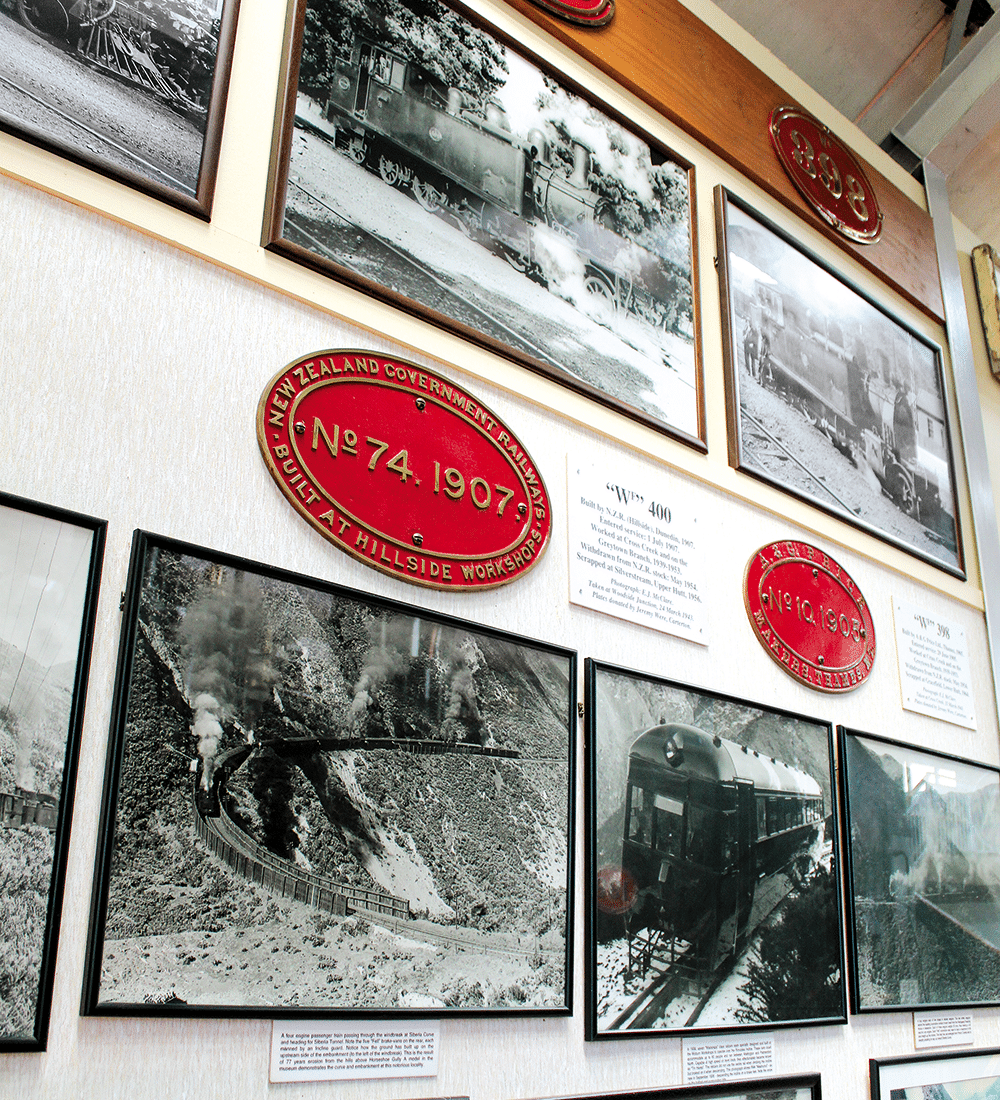

I was interested to discover Noel’s photo on the wall, alongside other volunteers who had been instrumental in bringing the Fell locomotive back to life. It took them eight years, from 1981 to 1989, and 9,000 hours of voluntary work to fully restore the Fell H199.

As I gazed at this immaculately preserved example of 19th century railway history, I thought: What an impressive feat!

John remarked, “It was a real Men’s Shed effort!”

A railway community

Cross Creek was a marshalling yard serviced by a community of railway workers and their families. The workers prepared the Fell engines and trains for the 305- metre climb to the summit. There were several work depots at the Cross Creek where they carried out repairs plus ashpits, coal bins, water vats and a three-way turnout leading to the engine shed.

Stepping into a theatrette at the museum to watch a video, we learn more about life in this railway community. The narrator tells us, “Many workers have spent the happiest years of their lives at the creek. There’s been talk of doing away with the incline for years. Last year they began working on a tunnel under the Remutakas, and although it’s a hard life here, I reckon we’ll miss the place when it’s closed. We’ve got a fine lot of fellows here, some of the best coal shovelers in the dominion. I remember Alex Stevenson, who could empty an LA wagon (8 tonnes) in half an hour. This goods train coming in is bound for Wellington, and at 250 tonnes, it will be a full load and require four Fell engines. The yard layout at the creek is designed for marshalling trains coming and going on the incline. A Fell can pull 65 tonnes, and each engine is cut into the train ahead of its allotted load.”

You can imagine how the railway united a tiny community of 120 people. Former residents of Cross Creek have many memories of their life. Jessie Holmes recalled, “You had to juggle your washing to suit when the trains went up the hill. If you left them out when they worked with the engines, the smoke turned your clothes black.”

Another resident, Bill Peters, remembered, “The school was never locked. I remember when it was windy; the whole building used to shake. When I arrived, there were 28 children on the school roll, and it gradually dropped until there were only 10. I was supplied with great big lumps of railway coal; I used to plonk one on to get the fire going. I’d get there in the morning, and it would last most of the day.”

Today, Cross Creek doesn’t exist, but the area has become part of the Remutaka Rail Trail opened by the Department of Conservation in 1987. Remnants of the former settlement, such as the concrete foundations of the locomotive shed and the turntable pit, can still be seen.

A tunnel transforms travel

It was a mammoth task to drill a tunnel through the solid rock of the Remutaka Range. Delayed by the worldwide economic depression of the 1930s and World War 2, work on the 8.8km tunnel finally got underway in 1948. When the tunnel opened in 1955, it reduced travel time between Upper Hutt and Featherston from three hours to 45 minutes.

The jubilation people felt when the tunnel was pierced is described in the video. “The team tackled the last 18 feet of rock in the tunnel at midnight. With its removal, the dream of half a century was becoming a reality. What had seemed an impregnable natural barrier to fast transport between Wairarapa and Wellington had fallen to the skill of modern engineering. It was a big step forward.”

Railway history

Four Fell locomotives were built in 1875 Bristol, England, and two in 1886 in Glasgow, Scotland. Seven Fell brake vans were built for use on the incline as well.

Trains often required five of the six Fell engines interspersed throughout their length, plus brake vans to haul them to the summit.

Operating speeds on the incline were 6.4km/hour when climbing and 16km/hour descending.

Motorhome parking

To the rear of the museum, there is an area for self-contained motorhome parking; maximum stay is 2 nights. This is run by the South Wairarapa District Council. swdc.govt.nz

Fell Locomotive Museum

Corner of State Highway 2 and Lyon Street, Featherston. Hours: Saturdays, Sundays and public holidays 10am–4pm. Adults $6, Children $2, Family $13. fellmuseum.org.nz

Looking for motorhomes or caravans for sale in NZ? Browse our latest listings here.