Nestled between Mangakino and the Pureora Forest turnoff on State Highway 30 resides Pouakani, the world’s largest tōtara and one of the greatest living monuments in New Zealand.

The sign in the car park at the Pouakani Forest Tōtara Reserve is just as unremarkable and weathered as it was when I first set eyes on it in 2011. You wouldn’t think this modest notice is the gateway to the home of a living monument: Pouakani, the world’s largest tōtara tree.

This impressive tree, standing 42.7 metres tall with a 12.18 metre girth, has an estimated wood volume of 203.7 cubic metres. The last major volcanic eruption showered the Pureora district with ash about 1800 years ago, with the age of Pouakani believed to be around 1000 years.

From an aerial perspective you can see where Pouakani grows: within a narrow island of native forest, wedged in by acres of pine forest on one side and pasture on the other. It illustrates the extent of the loss of the indigenous forest and this tree’s survival against all odds. It’s a mystery that this giant survived the bushman’s axe when the logging of native forests was in full swing. But it did.

Walking through the forest

To reach this monumental conifer is a 20-minute walk into the bush, wandering along paths made spongy by forest litter. Over the course of the walk it’s a pleasure to listen and observe the surroundings carefully: the din of chorusing cicadas, ropey supplejack vines dangling from above, astelias (bush lily,) orchids, and ferns nourished by their hosts. Overhead, sunlight flickers and dances through shifting curtains of green.

With no-one else around, we enjoyed the solitude, and as we walked, we attempted to identify some of the many surrounding plants and trees. A tree, upended, perhaps from a storm, revealed its decaying heart; another has fallen and come to rest into the fork of the other, as if in some naturalistic embrace.

And along the track, Pouakani rises majestically through the foliage. I felt a sense of awe as I approached. For a better view – and to fully embrace the moment – I lay on my back, marvelling at the heavily-knotted columned trunk, ancient and gnarled, with convoluted roots and deep cavernous holes that suggest the original ground level is several metres below the current forest bed.

It’s impossible not to feel awestruck at this healthy tree, not least for her longevity, with a lifespan stretching from when this area was solely nature’s domain to the present day. In Aotearoa, we don’t have many old buildings to remind us of our past, but we do have ancient natural wonders in the shape of trees such as this beauty.

As I walked around Pouakani to experience the sheer size of her girth, I noticed a large branch had broken off and come to rest beside her. Closer inspection reveals many more broken-off boughs that are showing new foliage; this mammoth has survived far worse than the odd broken branch, and new growth continues.

We farewelled Pouakani and followed our way back from where we came, picking our way carefully over twisting roots and the humps and hollows of the track. As we emerged into sunlight, the sound of a truck along the road snapped us out of our pleasant trance.

The Pouakani walk is a 40-minute round trip from the car park. Make sure you allow for plenty of time to enjoy this historic tree. It would be good to see new signage that reflects the significance of the Pouakani and her considerable mana.

Protecting our native forests

Pureora Forest, which is not far from the Pouakani tōtara, was one of the last native forests to be opened up for logging in 1946, and became the scene of anti-logging protests during the late 1970s. Protestors built platforms in treetops, sat in front of trees, and hid in the bush to prevent the foresters from doing their work. In the end, faced with such fervent opposition and growing public and political pressure, the Forest Service backed down and halted logging of all native trees in Pureora Forest in 1978, then finally stopped in 1982. The Native Forest Restoration Trust developed the park into the natural environment we enjoy today.

A sign at the site of the historic protests speaks of this campaign, stating, “Many people believed it was wrong to log what was left of our native forests, and in the 1970s, their simmering anger boiled over into action. Vigorous, highly-publicised campaigns were held at Maruia, Whirinaki and Pureora. These names still conjure vivid images for many people: magnificent forests, protestors climbing trees and petitioning parliament; angry loggers defending their livelihood.”

A central figure in this movement was conservation activist Stephen King, sometimes referred to as Tarzan because of his ability to scale trees barefoot.

Of those days, Stephen said, “We didn’t want confrontation; we just wanted to get the message across to the people of New Zealand and the politicians.”

And in that, they were successful; logging stopped for good in 1982.

An expert opinion

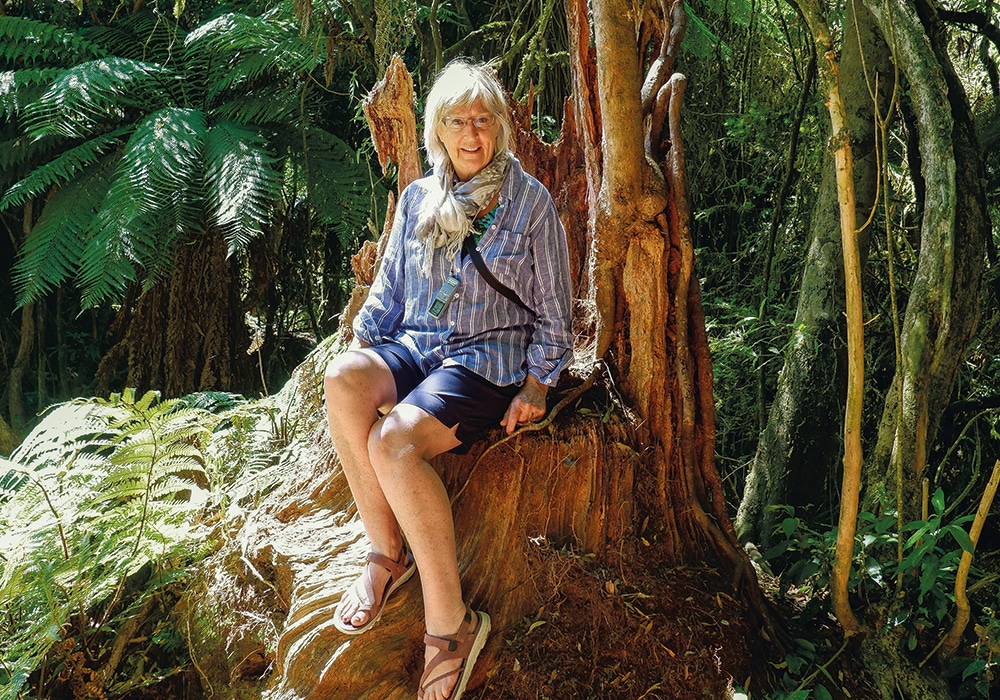

My first visit to Pouakani in 2011 was with botanist and author Dr Philip Simpson on a field trip to the Central North Island, the home of some of NZ’s largest tōtara. I’d photographed many tōtara to contribute to his book, Tōtara: A Natural and Cultural History, published in 2017.

Philip explains that seeds or debris at the base of a tōtara usually reveals whether the tree is male or female. He believes the Pouakani tōtara is most likely female.

Listening to his expert knowledge gave me an in-depth perspective of these trees, the surrounding podocarp forest, and the cultural and spiritual meaning of the forest for Māori. I also discovered New Zealand was built around the timber milled from our native forests, particularly tōtara, because of its sheer size and quality.

Philip says, “Tōtara was the number one timber for the evolution of both the culture of iwi (for waka and carving) and the pākehā culture that followed (for houses, fences, railway sleepers and telegraph poles). A family could get off the boat with an axe and build a life from the tree.”

Philip dedicated eight years of his life to writing his book on what he says are the most magnificent of New Zealand native trees. “Approaching a very old tōtara gives me a sense of pilgrimage – a journey to a sacred place,” he says. “An old tree has a special presence, the spirit of life. An old tōtara is also humbling, instilling reverence for its endurance, awe for its size, amazement that it has stood for a thousand years, thankfulness for what it has lived for ecologically. I think of what it has lived through: eagles in its massive boughs, moa eating its seeds beneath, enormous snow and windstorms; prolonged droughts and earthquakes; the arrival of humans; possums browsing its foliage; fire and nearby logging. An old tōtara has command over the bush like a leader, a chief, a rakau rangatira. It’s impossible to dismiss it as ‘just a tree’.”

More Information

Location: Pouakani tōtara is located one hour from Taupo on State Highway 30 (20 minutes south of Mangakino) and one hour to Pureora Forest Park.

Pureora Forest: Situated between Lake Taupō and Te Kuiti, the 760 square km (78,000ha) Pureora Forest Park is a remnant of the native podocarp forests that once covered most of the central North Island. When you visit Pureora it will give you an idea of what New Zealand would have looked like thousands of years ago.

Within the park, there are many trails of varying grades to enjoy for walkers, cyclists, and mountain bikers. There are huts available for overnight stays.

Here are a few easy-to-access highlights:

Tōtara Walk – an easy 30-minute loop walk with giant trees and many native birds. The Timber Trail starts beside the Tōtara Walk.

The Buried Forest – A five-minute walk to see trees that were knocked over, buried, and preserved by the Hatepe volcanic eruption that occurred 1800 years ago. The Buried Forest was discovered in 1983, having been accidentally uncovered by a digger.

Forest Tower – A 12-metre treetop platform was built near the site of the 1970s protest site. Here visitors can climb up and get a bird’s eye view of the forest and listen to bird calls; see if you can identify the various species.

Two relics from milling the forest: Vintage Steam Hauler and tractor. Used to haul logs from the forest for milling. Historic Crawler Tractor In the 1930s and 1940s this two-ton Caterpillar tractor was used to recover split tōtara posts and battens from the bush.

For a comprehensive brochure on Pureora Forest Park: heliwhirinaki.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/pureora-forest-park-brochure.pdf

Also worth checking out:

Mangakino, 20 minutes from Pouakani, is a small town on the banks of the mighty Waikato River. It was built in 1946 as a support town, created as part of the Waikato hydroelectric power scheme. Similar towns, Whakamaru and Atiamuri, still exist today.

Mangakino is a water baby’s dream; it’s an excellent destination for water sports, kayaking, boating, wakeboarding, and fishing. The Waikato River Trails are near here too. lovetaupo.com/en/operators/waikato-river-trails

There is free lakeside camping at Mangakino Recreation Reserve.

The Timber Trail: The 85km long Timber Trail starts in Pureora Forest and finishes in Ongarue. lovetaupo.com/en/scenic-attractions/timber-trail

Source notes: Quoted with permission by Philip Simpson, author of Tōtara – A Natural and Cultural History. Auckland University Press, 2017.

Looking for motorhomes or caravans for sale in NZ? Browse our latest listings here.