From the motorhome parked next to us hurtled a leggy teenager, her face contorted with rage. Long blond hair swirled around her bare shoulders like bleached seaweed. With one hand she held aloft an electronic devise, the focus of her rage.

“Whatddaya mean no signal?” She bellowed to the sky.

Placatory noises came from inside.

“Well I’m not staying here for two days with no signal,” yelled the she-devil. “I’m going home. I hate this hell hole.”

I guess things are only as you believe them to be. Hell for an adolescent was heaven to me.

Two hours before, on the way to the supermarket in Putaruru, I’d fallen in beside a short chubby lady carrying a large shopping basket. She was, she’d told me, a local. I asked her what there was to do around Putaruru.

“We go up to Lake Arapuni to fish at weekends,” she’d said. “You been there?”

Been there? I’d never even heard of it.

“Better put that right then,” she’d grinned. “It’s a great place.”

So here we were in Arapuni heaven, parked on the Jones Landing Reserve on the very edge of a silky stretch of water and blissfully out of reach from the outside world. When the she-devil eventually came to terms with her outrage, the only sounds were the occasional honk from a gaggle of black swans making a silver trail as they cut across the dark water.

Lake Arapuni, around 30 kilometres from Putararu or 65 kilometres south-east of Hamilton, is one of a chain of man-made lakes on the Waikato River, which were formed as a result of the Waikato hydroelectricity scheme.

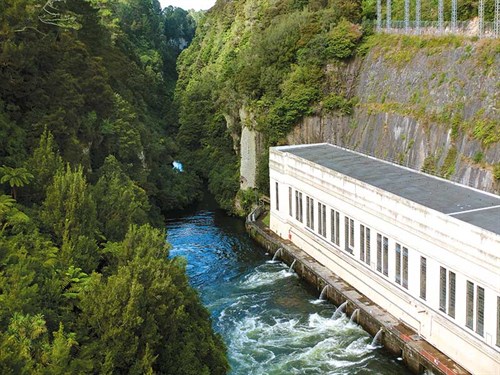

The 64-metre-high Arapuni Dam was the first of eight to be built on the river. Construction began in 1924 and by 1929 the power station was operational. The station now has a category one listing on the Historic Places Trust.

I walked across the dam wall on the road that runs along its ridge and was mesmerised by a spectacular view down a bush-shrouded gorge that forms the neck of the lake. On an adjacent road RVs can park overnight in a small area that is cupped by native trees.

There is an even better view from the massive swing bridge that straddles the river near the centre of Arapuni Village. Built to take construction workers to the powerhouse site, it swoops across the thrashing water of the Arapuni Gorge from one sheer cliff to the other. I paused mid-swoop and below, to my left, was the solid rectangular powerhouse that almost becomes one with the cliff face. On my right, a gut-churning 150 metres below my feet, was the roiling water of the Waikato River as it plunged towards its next destination.

During WWII it was deemed prudent to camouflage the powerhouse lest it be blown to bits by marauding Japanese bombers. On a billboard, a photograph of that time shows how it was prepared for the worst. A mass of foliage and plantings obscured its roof. The sides were painted in camouflage colours and concrete cones were placed over the generators. In the village, different types of generators created massive smoke screens that blotted out the dam and the buildings. Nothing happened of course.

The early construction workers would probably have made Arapuni a lively place. Today, there’s not much there – just a cluster of houses and a cafe called Rhubarb that is a stopping off point along the increasingly popular Waikato River Trail.

Back at camp, things had also taken a turn. It was a long weekend and we were no longer alone with just the teenager and her family. I liked the change. Next to us an extended family from farms up the road had pitched their various caravans, tents and awnings. I sat contentedly under my own awning and watched a pageant as entertaining as any TV show.

Fishers hauled out one yellow-bellied eel and two trout and the children caught small rudd in their nets (the more, the better – these introduced fish are destructive water-pests). Jed, a small wiry boy about five years old, ran a fishhook through his thumb. His Dad grabbed a pair of pliers and had it out in a jiffy. Jed howled and examined his damaged digit.

“Stick it in the water, mate. You’re OK. You’re one tough guy.”

I watched Jed manfully trying to be tough. His howl turned to a whimper.

His mother paddled her kayak closer to the bank.

“Don’t worry boy,” she called. “Be worse if we cut it off, eh?”

“S’pose,” said Jed. A minute later he was off as if the event had never happened.

A few minutes after that, it was mum’s turn when her kayak suddenly overturned. She was a large woman and she rose to the surface of the water like a titanic balloon. Everyone doubled up with mirth.

Out from a jetty, a small island supported a knot of trees and children swung from their branches like jumping spiders and plunged into the water.

On the north-west side of the lake are two more wonderful lakeside freedom-camping sites set among tree ferns, kanuka and oak trees – Bulmers Landing and Arapuni Landing. In the still air children from Jones Landing on the eastern bank and those in the western camps could call quite clearly to each other across the water.

Lake Arapuni has a lot of choice when it comes to camping, possibly as a concession for interfering with the river in the first place. On the west bank at its southern end is the appealing Arohena DoC camp on the water’s edge. There’s a small charge for staying there. The road into it has a gravel surface and is narrow and winding so those with large rigs might find the access a bit daunting.

North of Arapuni village, along Horahora Road, is Little Waipa Domain on the bank of the Waikato River. This is also a pretty spot and has a boat ramp, ablution facilities and free overnight parking.

A little inland from the lake’s eastern shore on Waotu South Road is the Jim Barnett Reserve, which has quite a different character to the lakeside areas. The lake’s hinterland, which is now a place of rounded hills and pea-green grasslands populated by Fresian cows, was once covered in great swathes of native forest.

And then early last century, the axemen and sawmills came in. Jim Barnett Reserve, 25 hectares in size, was rescued from the final chop by Walter Barnett and his son Jim who once owned the land. It is regenerating well and 13 well-defined, winding tracks take walkers past the totara, rimu, tawa and rewarewa trees that escaped the slaughter.

In a clearing on the edge of the forest is a grassy camping area – a peaceful spot among whispering trees that are populated by increasing numbers native birds.

We spent one more night at Jones Landing and awoke next morning to a change of scene. Dense Waikato cloud was curling up the ravines and rolling like gun smoke along the rocky ridges. The water birds had taken shelter. There was no wind, no sound except the dripping trees and we were eerily alone.

Lake Arapuni had become a dreamland that had all but disappeared into an ethereal fog. We decided then, that heaven was more likely to be found by going home.

Never miss an issue of Motorhomes Caravans & Destinations magazine. Subscribe here.