Waiting in the old New Plymouth railway station in the early hours of the morning was for me a common occurrence.

Every school holiday break throughout my youth, I would catch the New Plymouth to Auckland railcar destined for extended family in Ohura, where I had spent my early childhood.

Sometimes the guard would wake me as I slept on the hard wooden bench in the waiting room. Other times I managed to stay awake to see the railcar thunder into the station from what is now Kawaroa Close at around 2am.

I still remember the coziness of the overly-heated interior, the heavy red vinyl seats that clunked when you turned them to face the other way, the gritty cold linoleum on the floor and that distinctive smoky railway smell.

It seems almost silly now, but the immediate world for a 14 year old was a big place once you left the familiarity of home.

Leaving the bright city lights of New Plymouth and heading into the dark unknown was exciting and adventurous, a really big deal, although in reality it was only a four-hour rail trip into the back blocks of Taranaki.

International travel in the real world was still a number of years away.

That railway line I came to know so well was the Stratford-Okahukura line or the SOL, as it was more commonly known. And, despite all those journeys being at night, I still remember the high points: stopping at the brightly lit and busy stations of Lepperton, Inglewood, Midhirst, Stratford, Te Wera, Whangamomona, Tahora and Ohura, plus unscheduled stops at farm gates to pick up passengers — usually other school kids doing exactly what I was doing. And I remember the tunnels, all 18 of them from Pohokura to Ohura. You knew when you had entered them because your ears popped from the sudden change in air pressure.

Then there were the pig hunters with their guns and dogs being picked up and dropped off in the bush somewhere, and the newspapers thrown from the railcar missing the farm gates and possibly ending up in a tree or water trough.

Today, except for the rails, tunnels and bridges, it has all but disappeared. Gone are the red Fiat railcars, the New Plymouth railway station and rail yards, and all the other stations along the line, bar Stratford. Rural settlements became ghost towns as the residents moved away. And the freight trains finally stopped running as the track deteriorated and became unsafe. Finally, in 2009, the SOL was closed to mainline traffic and left to the elements.

This would have been the end of the story but for the forward thinking of entrepreneur Ian Balme. A chance-hunting trip near Ohura set off a chain of events that saw an ailing and disused railway line come back to life in the form of a tourism adventure using rail carts. From Stratford to Okahukura you can now self-drive a specially-adapted cart along the same rails as yesterdays railcars and freight trains used.

Today I am joining Forgotten World Adventures on one of its tours, called 20 Tunnels, which follows the route from Whangamomona to Okahukura. Van Watson, the operations manager of Forgotten World Adventures, who is busy cleaning the windscreens of 11 parked-up railcarts, welcomes me. It will be a long day for him. He's already driven from Taumarunui and will later go on ahead of us to set up morning tea and lunch and meet the carts at Okahukura to return me to Whangamomona, before I head home to Otorohanga. At exactly 9.30am a bus pulls up and 24 excited people spill out onto the platform, along with our guide Maree, who I will be riding with in the first cart.

After the safety brief, our convoy is off on what turns out to be a spectacular trip in terms of scenery, history and forging new friendships. No sooner had we negotiated the first curve out of Whangamomona we all came to a grinding halt at the first of several rail crossings. A bull had taken up residence on the tracks and seemed determined not to give way until Maree chased it into an adjoining paddock.

Rail crossings are dangerous places, so as a safety precaution Maree guided each of the carts across until our convoy was clear. From there it was clear passage through drought ravaged farmland until we reached our first tunnel (actually number four, just short of Tahora) for our first scheduled stop and a history lesson.

“All of the 20 tunnels we will be passing through today were hand dug, including this one,” says Maree to a captive audience. “Number four is actually quite short, unlike number 24, but I am sure by the time we get there you will have appreciated the stamina and sheer hard work the builders of this railway must have endured.”

As it turned out one of the travellers had a late friend who had worked on this very tunnel during the railway's construction. It was then that I noticed everyone on the trip were seniors with an average age of around 60 or so years.

“Most of our clients are in this age group, as it gives them an opportunity to experience adventure tourism that is easily accessible to them,” says Maree. “Our oldest client to date was in her mid-nineties.”

Earlier I had met 92-year-old Joan Allen and her sister Betty Churchill, almost 90, who were so full of life with infectious personalities to match, it was hard to accept that they were in their nineties.

“At Tangarakau there is a viaduct where you can bungy jump,” I quip.

Betty leaned forward and looked me straight in the eye, “Oh lovely, my dear. Sign us up for a tandem.”

Never lock horns with an adventure-seeking 90 year old — you will always come off second best.

Three tunnels and a viaduct later, we glided into Tangarakau for our morning tea break of hot coffee and muffins. At each stop there are newly-built plywood long- drop toilets, which brought back childhood memories. All that was missing was the sound of blowflies.

Newly refreshed, we were off again on our adventure.

“The next few kilometres are the remotest parts of the line and with the biggest concentration of tunnels, all dug by hand,” says Maree. “And there is nothing else but bush, goats, feral deer and wild pigs.” This must have been where the pig hunters got off the railcar with their dogs.

After travelling through several long tunnels we emerge back into the familiar sight of farmland coloured a light shade of brown. It is here the disuse of the line and its subsequent lack of maintenance is evident. Weeds, especially the nodding thistles and a type of purple statice, have all but covered the line for several kilometers.

This would be a common sight along the rest of the route as well as slips and broken branches falling onto the line that Maree and I cleared away before proceeding.

After encounters with yet another large bovine and a mob of five sheep on the line, we pull into the 'village' of Tokirima where lunch was spread out on two cable drums perched on the original station platform. A tarpaulin roof shaded us from the increasingly-hot autumn sun, while across the track was the now familiar plywood long-drop toilet.

Heading off again, we passed through the beautiful countryside that is Eastern Taranaki/King Country toward Ohura. This was the part I had been looking forward to. I still had clear memories of being there as a teenager.

Pandemonium would ensue every time the railcar pulled into the station. Luggage trolleys would clunk along the platform to be loaded with bundles of newspapers and crates of fresh milk in bottles and the stationmaster would fuss with mailbags going on, and coming off, the railcar. Farm dogs would be barking from the trays of utes parked nearby and people would be everywhere, boarding the railcar or leaving.

And there in the middle of it all would be my aunt, just 30 years old at the time, resplendent in her gumboots and bright blue Swandri jacket.

Opposite the brightly lit station were several sidings that were always full of wagons and stock cars, with their timber slats, a large goods shed, and several old-style railway houses. Just past the station was a row of ganger huts where the single railway workers lived and at each end of the complex were the large signal towers with their hooded lamps, red, yellow and green. There was even a water vat that serviced the odd steam locomotive that was so common back then.

But here in the present I was in for a big shock as we exited the tunnel on the approaches to Ohura. It was all completely gone, totally stripped to its core, with nothing remaining. The entire railway infrastructure has disappeared and the only thing remaining in its place was a slightly vandalised sign erected by Forgotten World Adventures.

We continued on across the rusty, lichen covered bridges I used to cross on my way to school, and past the old abandoned house we once lived in, with traces of the original paint still clinging to it in places. Yet, despite the welling of sadness that accompanied the myriad memories, there were two more highlights to come.

Just short of Matiere we came across newborn twin goats, seemingly trapped half way up an embankment. Much discussion followed among our group — should we take them or leave them? Surely the mother must be nearby… In the end we left them there, when Maree decided she would check in on them when she next passed by with a tour group.

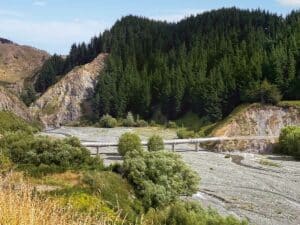

My last highlight for the day came on the other side of Matiere, at the portal of the most scenic tunnel on the line, number 20. Built of brick and covered in creepers with vines hanging down across the opening, it reminded me of an English castle with its ornate formal gardens. The rails coming out of the tunnel were embedded in a soft carpet of moss, lichen and buttercup, before spanning the river on a solidly-built bridge with curved metal sides. I photographed each of the 10 railcarts as they came out of the tunnel and onto the bridge, creating the most beautiful images of the day.

From here we slowly climbed up into the Okahukura Saddle, to the longest tunnel on the line, the scene of the original derailment that forced the lines closure. Long, cold and damp, it took five minutes to get through the tunnel. If you get the chance, keep an eye out for an interesting piece of graffiti art at the exit.

From the tunnel it is an easy glide down to the finish line, just short of the combined rail and road bridge where the SOL joins the Main Trunk Line at Okahukura Junction.

It was a long day, almost eight hours on the rails, yet it flew by as if it had been minutes with great weather, beautiful scenery, sadness, nostalgia, wonder, excitement, the unexpected, and great company. These are the hallmarks of this adventure.

The SOL railway played a major part in my growing-up years and to see all of it up close and in daylight was exceptional. It would seem that the Grand Old Lady that is the SOL still has a lot of life left in those rusty rails.

For the latest reviews, subscribe to our Motorhomes, Caravans & Destinations magazine here.

Raglan: winter beach life

Mel de Jongh discovers that Raglan is not just a summer destination and offers plenty to spark joy over the winter months