They rise up on the horizon like giant monolithic towers from a science fiction movie. At night, they are brightly lit like Christmas trees and when coupled with the flames of a flare burn off reflected in low cloud, they look almost apocalyptic. These are the distillation and cooling towers of the Methanex plants, one north of Waitara, and the other inland on the banks of the Waitara River.

Built in the 1980s during the ‘Think Big’ era, they are now almost as permanent a fixture on the landscape as Mount Taranaki, often photographed in the background. For anyone coming into Waitara from the north at night, the light show that is Methanex is a welcoming beacon to the area.

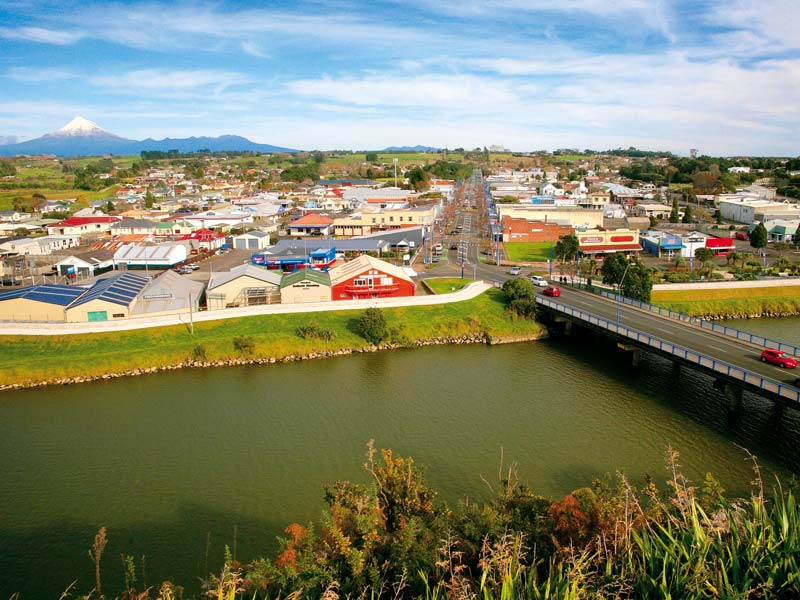

Just like the river that divides the town in two, division seems to be a legacy for Waitara that goes back to earlier times. Written in blood and conflict, the area has a history that is both disturbing and savagely unsettling. Nowhere is this more apparent than during the fall of Pukerangiora Pa in 1831.

Built high on a bluff overlooking an abrupt bend in the Waitara River, the ancient Pa occupied a magnificent setting, its natural beauty marred only by the atrocities committed there. In 1831, a marauding Waikato war party trapped some 4000 people within the pa fortifications. After a three-month siege, 1200 were killed as hunger drove them to seek escape. Many were enslaved, but one of the most horrific aspects of the siege was the mass suicide of women who jumped over the cliffs into the river taking their children with them.

Pukerangiora is a spectacular place to visit, and for me, terrifying as well. Standing at the edge of the cliff behind the fence, it is hard to comprehend the terror and hopelessness that drove mothers to jump with their children onto the rocks 100 meters below.

Apart from the annual WOMAD powhiri, the other highlight in Waitara is the annual Puanga Festival. Now in its 11th year, the festival brings together primary, intermediate, and high school kapa haka groups in a three-day competition with a chance to win a trophy for their school. Competition is fierce with many schools vying to keep their trophies from previous years.

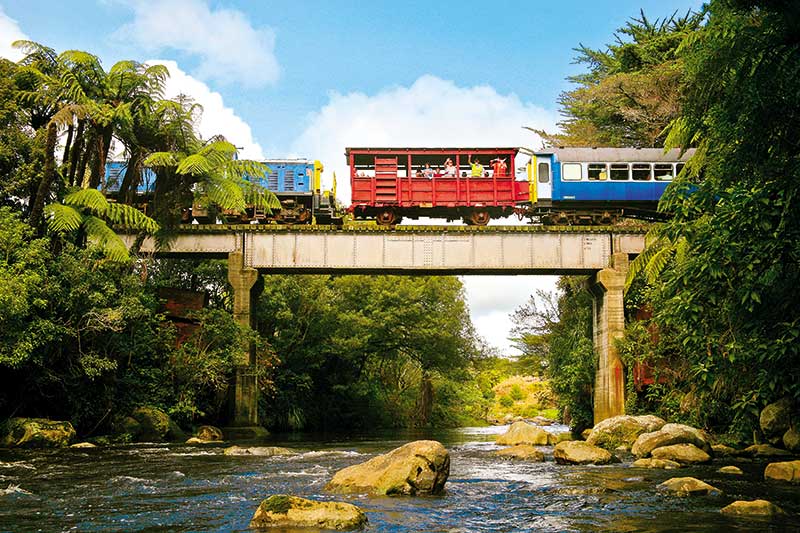

I joined the Waitara Railway Preservation Society for one of their excursions that takes tourists from Waitara to Lepperton and return. The society is a group of railway enthusiasts not afraid to ‘think big’. With the closure of the freezing works in 1997, the Waitara Industrial Branch Line was no longer used and fell into a rapid decline until the society bought the line in 2001 with a view to preservation. Reminiscent of a point-to-point model railway, the society runs a 45-minute tourist excursion every first and third Sunday of the month. I joined the society in April on one of the last excursions for the current summer season this year.

From the moment you enter the now pristine, restored former Tahora railway station to climbing aboard the diesel locomotive with the driver, you are whisked back to a gentler time. The attention to detail and safety is remarkable. The guard, driver, and ticket puncher are dressed in the appropriate period uniforms, spoilt only slightly by the bright orange and lime

safety vests. At the start of the excursion, the train was filled quickly by children—noisy and in the excited high spirits that only a short train ride can induce.

From the former site of the now gone Waitara railway station, the line crosses the first of the eight-level crossings before a gradual climb out of the Waitara valley to the SH3 underpass at Big Jims Hill, affectionately known as the lines ‘tunnel’.

This section of track has a gradient of one in 40, the steepest gradient of any railway climb in New Zealand.

From the underpass, the track is level all the way to the lines highlighting the newly restored bridge crossing the Waiongana Stream.

At Lepperton, the train returns to the Waitara Road station where refreshments are served before returning. There are big plans ahead for this little railway with the restoration of its own steam locomotive already underway, making it even bigger in the future.

Like Patea down the line, the loss of the freezing works, the town’s biggest employer, has had a devastating effect on its economy. But with 30 odd years of ‘thinking big’ behind it, there is nowhere else to go but even bigger.