On another of her intrepid adventures around New Zealand, Jill Malcolm discovers one of her favourite types of destination – a tiny town with a big heart

“Oh, I’ve ‘done’ your country,” said a chatty Parisian the last time I was in that exuberant European city. He went on to tell me about his two-week Kiwi holiday. “I went everywhere – did it all,” he said.

I thought it wise not to mention that, in 25 years of intermittent travel around New Zealand, I couldn’t say I’ve ‘done’ it. Nearly every time we’re on the road, we come across places we have never been to before.

Earlier this year, Bill and I drove State Highway 83, the interesting route from Omarama to Oamaru that unfolds along the Waitaki Valley. If I’d driven his way before, I must have been asleep because I couldn’t remember anything of the delightful town of Duntroon, which lies close to the braided Waitaki River.

The village declares itself the epicentre of the ‘Vanished World’ so maybe it wasn’t there at all. The name, however, refers to a trail that leaves from town and meanders past important geological and fossil sites clustered in the Waitaki Geopark that extends as far as Oamaru. A geopark is an area of international geological significance and last May, this area was accredited status as a UNESCO Global Geopark (the only one in New Zealand).

But I’m ahead of myself. First of all, there was the village to unravel. Duntroon is also making a future from its more recent past. In its days as a service centre for local farmers, the buildings included a railway station and a gaol. The old gaolhouse is only marginally larger than a Portaloo and was built in 1910. It has since been restored and is now surrounded by a picket fence. In its only cell, a model of a hapless female prisoner lies for eternity on a very uncomfortable bed. Adjacent to this building is an even smaller shed where locals share their excess fruit and vegetables in return for koha. This gesture immediately endeared me to the spirit of this tiny town.

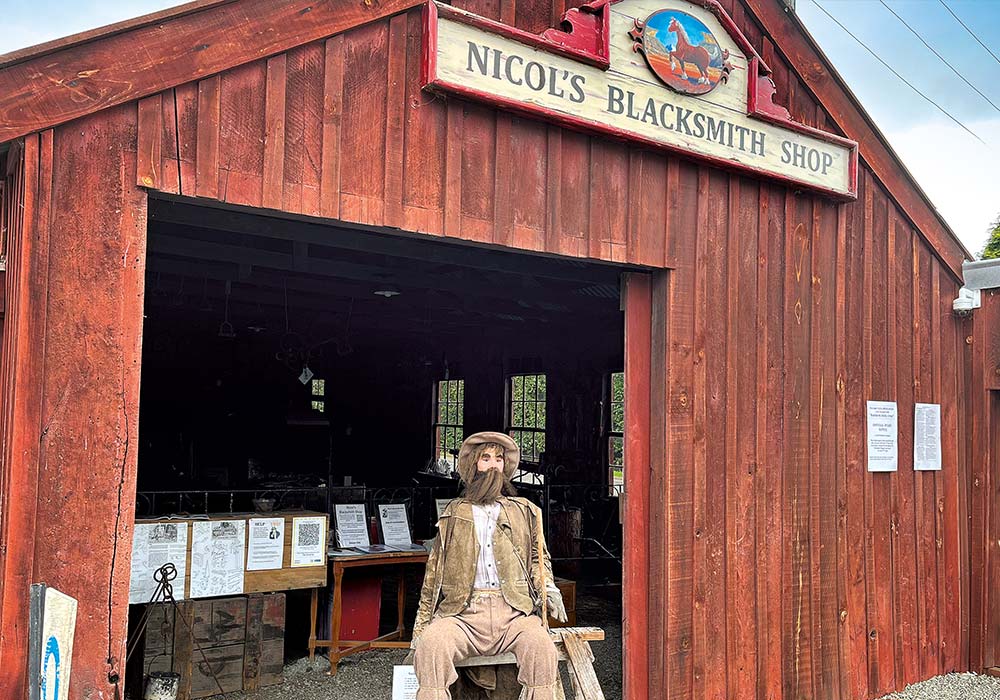

Across the road is Nicol’s Blacksmith shop, a rare survival of its kind, which has been operating as a smithy since the era of equine transport in the 1880s. It still houses all the tools of the trade. The furnace is fired up regularly and old skills are demonstrated by local volunteer blacksmiths who work the forge and create crafts for sale. Behind the smithy is a deep limestone cavern filled with running water, called the Brewery Hole. On its lip stands a life-sized moa made of steel. I’m not sure of the bird’s significance but an early settler briefly used the water for his small brewery and later, until its roof collapsed, it was the town supply. Thankfully, there has been no collapse of any part of Duntroon’s handsome St Martin’s Gothic Revival church. This elegant religious building on the edge of town, with its square-sided tower and pointed arches, was built of locally quarried limestone in 1901 and is one of the most photographed churches in Otago.

Then, four kilometres north, we came to significant limestone cliffs built up from dead sea organisms when the area was under the sea. Here, at the base of impressive honeycomb walls and bluffs that are drizzled with black rivulets, is rock art left by Māori who travelled through the valley hundreds of years ago and sought shelter in Duntroon’s shallow caves. The paintings are faded now and, in places, barely discernible but information boards depict drawings of how they once were.

After all this exploration, we needed a reboot and returned to the village centre to the flamboyantly pink Flying Pig Café for an excellent coffee and delicious home-made pies filled with home-grown beef.

A couple of years ago, the café was bought by a local couple who owned a berry farm. Their daughter, Sarah Kingsbury, had been a chef at Mt Cook Hermitage but had been laid off during the COVID pandemic and returned home to set about turning the Flying Pig into the delightfully homey café it is today. Figures of pink pigs fly across the rooftops and inside the café hangs a penny farthing bicycle, which is most likely a reference to the bike trail that passes through Duntroon. Known as the Alps2Ocean Trail, it’s the longest cycle rail in New Zealand, starting at Aoraki/Mount Cook and ending at Oamaru. It’s a hardy soul that tackles the whole length.

Now revived, we stopped in at Duntroon’s Vanished World Centre where, among fossil gazing, I learned, that 25 million years ago, New Zealand lay under a shallow sea and marine creatures swarmed all over this part of the country. Most notable among the fossils and replicas are a whale with four legs, penguins almost the size of a man, and a near-complete set of bones of a shark-toothed dolphin called Waipatia, which scientists painstakingly chipped from its Otekaike limestone resting place nearby. We picked up a trail map from there and headed off to explore. The first stop was the Earthquakes, where there are huge limestone formations resulting not from earthquakes, as first thought, but from ancient land slumps. Apparently, they hide many old bones and shellfish but the only evidence I found was the jawbone of a modern sheep.

After a short uphill walk through long grass, we found our first in situ fossil of whale bones poking out of the brittle limestone. They rest behind a protective steel grill.

Next up, across the Maerewhenua River, were the spectacular Elephant Rocks. You’d have to have the imagination of a stone to not see that these monumental grey humps, scattered over a peaceful paddock on private land, resemble petrified pachyderms.

Their bulky shapes were formed from sand on the seabed and gradually turned into rock over a mere 25 million years before being further sculpted by wind and rain. Continuing down the road, through a cleft in the rocks and behind a Plexiglass protection, were another set of fossilised bones, which were more easily discernible as a baleen whale.

Across the Awamoko Stream, the extraordinary Valley of Whales is another rich source of fossilised bones, none of them visible on a drive-through, but the long stretch of grey, black, and cream-coloured cliffs exposes sediments, which are layered like a trifle and track geology back in time.

Then on Dip Hill Road, dripping molten basalt once formed quirky, 40-million-year-old rock columns resembling man’s first attempt to build something like the Greek Parthenon.

We returned to the village and parked for the night in the quiet, sheltered Duntroon Domain, which has been set aside for campers and RVers and is maintained by local volunteers. Across the road is the renovated and remodelled Duntroon Hotel, which has survived on this spot since it first opened in 1881. We intended to have a drink at the bar and return to the motorhome for dinner but were seduced by the menu.

I had beer-battered blue cod and Bill feasted on glazed pork ribs. The meal was excellent and like the whole of his tiny town in the Waitaki Valley was an experience that’s unlikely to vanish from my memory any time soon.