Cromwell owes its existence to gold. Few people lived in the area prior to the discovery of 87lbs of gold by two prospectors in July 1862, but by the end of the following month, 2000 miners had descended on the hills bordering the Clutha River. The gold rush led to towns springing up, then just as quickly disappearing, leaving little more than

their names.

Quartzville, Carricktown, Bendigo, Welshtown, and others are now merely crumbling ruins on scarred, barren landscapes. The first miners staked claims, dug into the gravel by hand, then washed it in pans to find flakes and nuggets. After a few years, they began sluicing—building dams and water races that washed the land away, leaving strange cliff formations and rock tailings.

When the gold rush boom died down, these water races were used for irrigation of pasture and the development of a horticultural industry: fruit trees and vines. The miners had planted fruit trees for their own use and this expanded to include orchards of apples, cherries, peaches, apricots, and pears.

The fruit bowl of South

Cromwell, known originally as The Junction because it was sited where the Clutha and Kawarau Rivers met, was surveyed in 1863. The original canvas town of tents and schist shacks grew after a bridge was built to provide easier access. More permanent buildings were constructed along the busy main street of Melmore Terrace, and the town continued to thrive when the gold rush days faded, mainly because of the success of fruit growing.

Cromwell’s first Horticultural Society was founded in 1892 and the coming of the railway in 1917 ensured overnight delivery of fruit to Dunedin markets. In the Cromwell Gorge, orchardists found a microclimate where crops ripened even before those in Cromwell itself.

They began to grow apricots, plums, nectarines, and peaches. Descendants

of the original fruit growers who still lived and worked in the gorge in the late 20th century had to move away when the Clyde Dam was built, flooding the valley. However, there are still many orchards in Cromwell and the surrounding area.

Locals and visitors crowd to the roadside fruit shops and stalls and many orchards have pick-your-own areas. Cherries were in season when we visited in December and we were given a brimming bagful by motorhoming friends who were working in a cherry orchard.

Cromwell’s horticultural legacy is recognised by the town’s icon—the 13-metre-high, seven-tonne Big Fruit sculpture presented by the Rotary Club

in 1990.

Pinot Noir capital of New Zealand

Cromwell is not only known for its fruit. The first settlers planted vines, and this tradition has expanded and flourished in the last few decades. The Cromwell area is the fastest growing wine region in New Zealand with a speciality in Pinot Noir.

Many wineries open for tasting and sales; some also have restaurants where visitors can enjoy locally sourced ingredients in their meals. You can’t visit Cromwell without eating its fruit and drinking some of its wine.

The birth of a new town

While fruit growing has remained constant for 150 years, the miners and settlers of The Junction would not recognise Cromwell’s shoreline. What was once the confluence of two great rivers is now part of picturesque Lake Dunstan. Waters lap the lakeshore 40 metres above what were once tree-fringed valleys.

The construction of the Clyde Dam began in 1977, and by 1993, Lake Dunstan was full. Cromwell’s old bridge is deep underwater, supposedly with a Mark 1 Zephyr still parked on it. Cromwell became the ‘newest town in the country’ with the building of a new bridge, houses, and modern shopping mall.

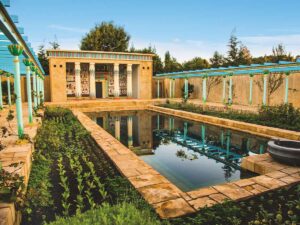

Part of Cromwell’s main street was lost to flooding but some grand old buildings were saved and rebuilt in Old Cromwell Town, Cromwell’s Heritage Precinct. Cobb & Co’s store, Jolly’s Seed and Grain Store, the Belfast Store, Argus building, and several others now sit safely above the water.

Wishart’s Garage and Murrell’s Cottage have been refurbished on their original sites. This area is a pleasant mix of museum-like buildings, galleries, workshops, designer stores, and cafes.

A farmers market is held here every Sunday from November to Easter.

Lake Dunstan—a haven for water babies

Lake Dunstan is a paradise for those who love water-based activities. The lake’s Clutha Arm (north of Cromwell), Kawarau Arm (south to Bannockburn and then west towards Queenstown), and Dunstan Arm (which goes to Clyde and the dam) cover 26 square kilometres and have a shoreline of 106 kilometres.

Boaties and jet skiers zip around. There are boats towing laughing children in inflatable donuts, waterskiers, windsurfers, and people just swimming—though the lake water is cold!

There is trout fishing at Lowburn Inlet and along the Dunstan and Kawarau arms. We found there are not as many freedom camping places around Cromwell and Lake Dunstan as there were a few years ago. However, there is an NZMCA park at McNulty Inlet and also a large freedom camping spot at pretty Lowburn where we spent Christmas.

The original settlement of Lowburn is now underwater but the church was moved inland and it now stands beside the waters of the Lowburn Inlet.

We walked up the steep 501 steps just north of Lowburn to the Lowburn Terraces, where the 45th parallel crosses Lake Dunstan. From the terraces and the peak known as the Sugar Loaf, we got amazing views up and down the lake.

We followed the walking track down through remains of gold mining tailings beside a water race to the Lowburn Inlet.

Cycling around

For those who prefer land-based activities, there is a lakeside walking and cycling track. One section goes north from Old Cromwell Town to Pisa Moorings, a lifestyle subdivision with willow-lined inlets.

In the other direction, the track goes along beside the lake to the Bannockburn Bridge, then continues along to Ripponvale. We cycled the different sections of this track on two separate days but keen cyclists could ride it in one day. Track descriptions and times are shown in a brochure available from the Cromwell i-Site. On the other side of the Bannockburn Bridge is an extensive area called the Bannockburn Sluicings.

There is a walkway here through what was once a busy mining area. Miners worked their claims in small syndicates and the high pillars of rock and earth that remain towering above the valley floor were the corners of their claims, left to prevent disputes.

Races, dams, sluiced cliff faces, tunnels, and caves are passed as the path wends its way through the workings. Some of the tunnels were mines before the landscape began to be washed away. High on the slopes above, what looks like a stone wall enclosing a paddock, is, in fact, the remains of Menzies Dam, once fed by races. Nearby are the remains of Stewart Town—some roofless rammed-earth houses the colour of the surrounding dusty hillsides—and, surprisingly, an orchard of pear and apricot trees planted by miners still bearing fruit.

After a couple of hours exploring the sluicings, we drove into the tiny settlement of Bannockburn. There are some buildings here dating back to settler times, including what is now a cafe and nearby, the pub.

The Bannockburn Hotel was first built in 1867 and holds the first liquor licence granted in Central Otago. The present building is full of old photographs and historical information but we came mainly for its beer garden, where we enjoyed long cold drinks while we looked down on Cromwell and Lake Dunstan.