Mention to fellow motorhomers that you are driving an hour north of Dunedin to spend a few nights in Moeraki and they are liable to look bemused for minute before offering an enlightened smile: “Aah, the boulders,” they’ll say.

More than anything else, the strange, rounded rock-marbles that line up along the beach about two kilometres from the village are the Moeraki Peninsula’s most famous feature. But for us, it was the whole area that was the lure: the cute harbourside village, the pa site, the unmanned lighthouse, the wildlife and Fleur’s Place – the restaurant that has become almost as well known as the boulders.

We took a side trip before we reached the Moeraki Peninsula, to find one of the other great treasures of this wild, wind-whipped shoreline. Shag Point, where the Horse Range tapers off to meet the sea, is one of the most accessible headlands on the east Otago coast, and 60ha of it has been set aside as a sanctuary for wildlife. To the north lies Katiki Beach and Moeraki Peninsula, and to the south, the mouth of Shag River. The point is also known as Matakaea, ‘place of wandering gaze’ – a name that precisely sums up how we spent our visit, for, gathered here on the mustard-coloured cliffs and tiny craggy islands, is an extraordinary collection of marine wildlife.

Further north, a turn-off leads from SH1 to the Moeraki village, tucked into a horseshoe bay carved out of the peninsula’s lumpy knuckle. The turn is indicated by a repainted old boat called The Leeane, which has reached her final berth in the middle of a paddock. And as we drove into the village along Haven Street, another rough sign pinned to a pole read: “Slow down”.

Already I knew the message was not just for driving. The first hint of a change of pace was in the name (Moeraki translates as ‘a place to sleep or dream by day’), followed by the first sight of this quiet, almost-forgotten corner of Otago being like a long sigh. The village is a drowsy hotchpotch of holiday baches and permanent homes, all gathered around a pretty north-facing bay scattered with colourful fishing boats. The wind dropped, the sea was soothed, and ropes of sunlight filtered down from behind thin clouds.

The population of Moeraki is only around 60 (although nobody knows the exact number), so there was little sign of life as we pulled into the Village Holiday Park. This camping ground should also be included among the charms of the peninsula. Like the village itself, it’s a slowed-down, friendly sort of place. Set above the road at the foot of a low hill, and bordered by pine trees, the grassy sites spread over two terraces from which there are glimpses of the fishing boats bobbing at anchor in the cove.

There has never been a large population here despite the wealth of seafood, edible seaweeds, and a good growing climate. This is probably because there is very little potable water. Pakeha arrived here in 1836, when a shore whaling station was established in a curve in the bay. It was the first European settlement in North Otago. At the turn of the century, it was fishing that sustained the town, but that too declined – many of the boats anchored in the harbor are now used for recreational fishing – although the crayfish boom kept going into the 1960s.

Isolated from the outside world, the village today (if a little low on population) seemed full of smiles. I’m sure it’s not paradise: it could no doubt be dismally cold and bleak in the winter. But any local person we came across seemed very happy to be there.

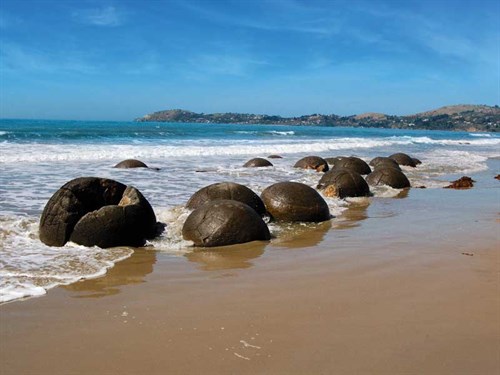

From the village, we walked about two kilometres along the Millenium Walkway, passing through tunnels of scrub on the edge of the cliff and along a magnificent arc of red-sand beach that leads to the famous bubbles of rock. These five-million-year-old concretions have crystalline centres, and their surfaces are ribbed with extrusions of yellow calcite. I had seen hundreds of photographs of these strange, spherical lumps strewn along the sand, but I still marvelled at the sight, seeing it in the flesh.

The other attraction to Moeraki is Fleur’s Place. In 1991, Fleur Sullivan came to this tranquil spot from Clyde to recover from a brush with cancer. As her health improved, her addiction for garnering wild food from the land and sea returned – she couldn’t help herself. Buying herself a caravan and a hawker’s license, Fleur began selling fresh fish and fish chowder on the old Moeraki wharf to anyone who wanted it. Fleur’s Place is now a charming, rustic restaurant of international acclaim, built around her philosophy for food: fresh, honest, and locally produced.

Indeed, like the food at Fleur’s, the whole Moeraki peninsula is unforgettable.