Along this beautiful harbour you’ll find spectacular kauri, and communities that retain a special character, writes Heather Whelan.

Explorers from Polynesia arrived in the Hokianga Harbour, possibly as early as 925AD. The navigator Kupe came on the Matahoura canoe, and his crew settled in the harbour. Kupe eventually returned to his homeland – the harbour’s full Māori name means ‘the final departing place of Kupe’ – but others followed in his wake, including his grandson, Nukutawhiti.

The harbour extends 30km inland from its mouth at the Tasman Sea, stretching from Ōmāpere to Hōreke along its southern shores, and from Mangamuka Bridge to Kohukohu and other small communities on its northern banks. The settlements cling to the waterside – travel was by boat long before there were roads – and many of Hokianga’s roads are still narrow and unsealed.

Towering trees

The Hokianga district is in the far north, about four hours from Auckland and 1½ hours from Dargaville. We travelled from Dargaville along SH12, the Kauri Coast route, to the Waipoua Forest. This is the largest remaining tract of native forest in Northland, and normally the road through the forest is busy with sightseers. However, the lack of overseas visitors was obvious as the road was deserted, and we pulled over a couple of times to photograph the roadside trees. We passed the Darby and Joan trees, standing sentinel either side of the road, before pulling into the carpark at the start of walking tracks to some of the biggest kauri in the forest.

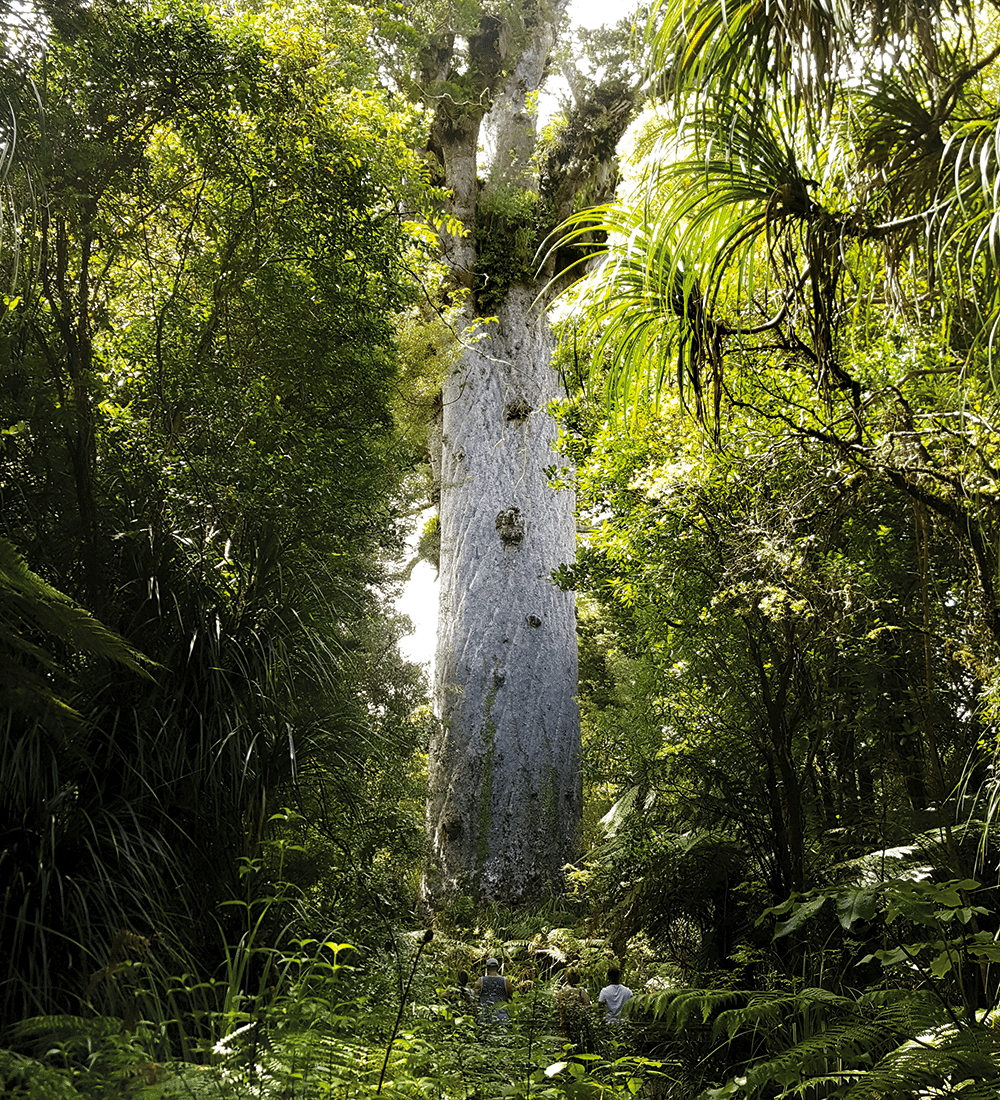

Logging and fire have decimated the ancient kauri that once crowded the forest, and it’s sad that now, when the remaining trees are treasured and protected, they are threatened by kauri dieback. Tracks to the Four Sisters and Yakas Kauri are closed to protect the trees, but the walk to Te Matua Ngahere is still open. Known as the Father of the Forest, Te Matua Ngahere is New Zealand’s second largest tree, and is between 2500 and 3000 years old.

After cleaning our shoes at the hygiene station, we wandered along the forest track, admiring all the trees. There were not only kauri but rimu, tōtara and other podocarp species, with neinei, keikei, ferns and mosses below. Thick rata vines clambered up host tree trunks. Suddenly, after rounding a bend, there was Te Matua Ngahere in front of us, massive and dwarfing the nearby bush. It’s almost impossible to show the size of these trees in photographs, but Te Matua Ngahere’s girth is 16.41 metres, and its total height is 29.9 metres.

Further along the road we stopped to visit the Lord of the Forest, Tane Mahuta. The walk to this giant is only a few minutes (it was 20 minutes each way to Te Matua Ngahere) and there were a few visitors here admiring the tree. We were beginning to get stiff necks after craning to look up at so many amazing trees, so took a small detour to another viewing platform that gave us a better idea of the tree’s size (nearly 18 metres to the first branches, and 4.4 metres in diameter). Tane Mahuta is younger than Te Matua Ngahere, around 2000 years old.

Seaside and sandhills

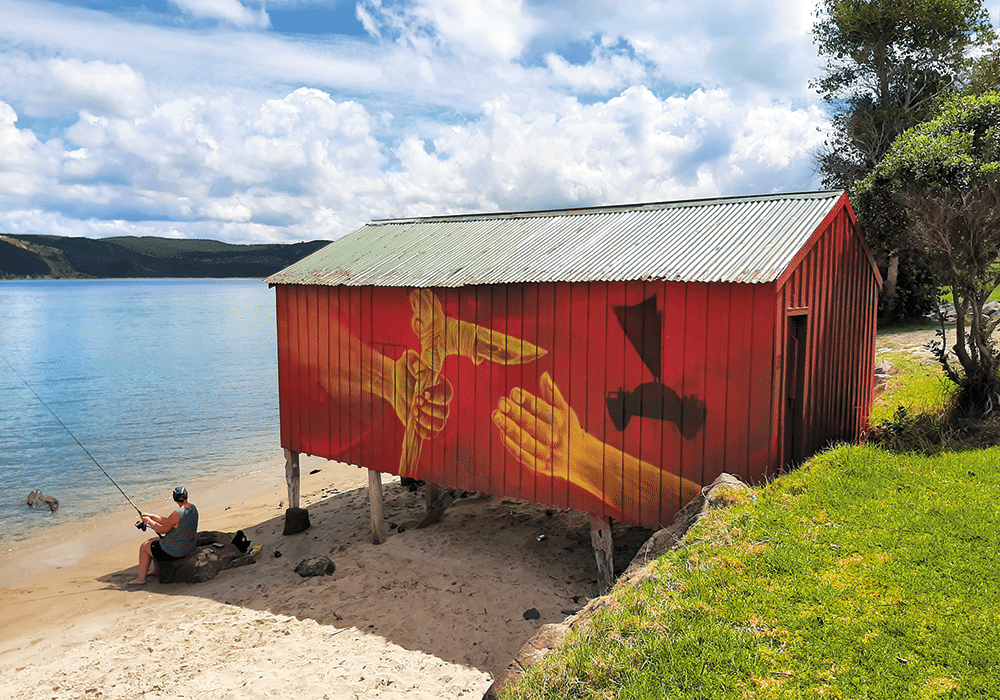

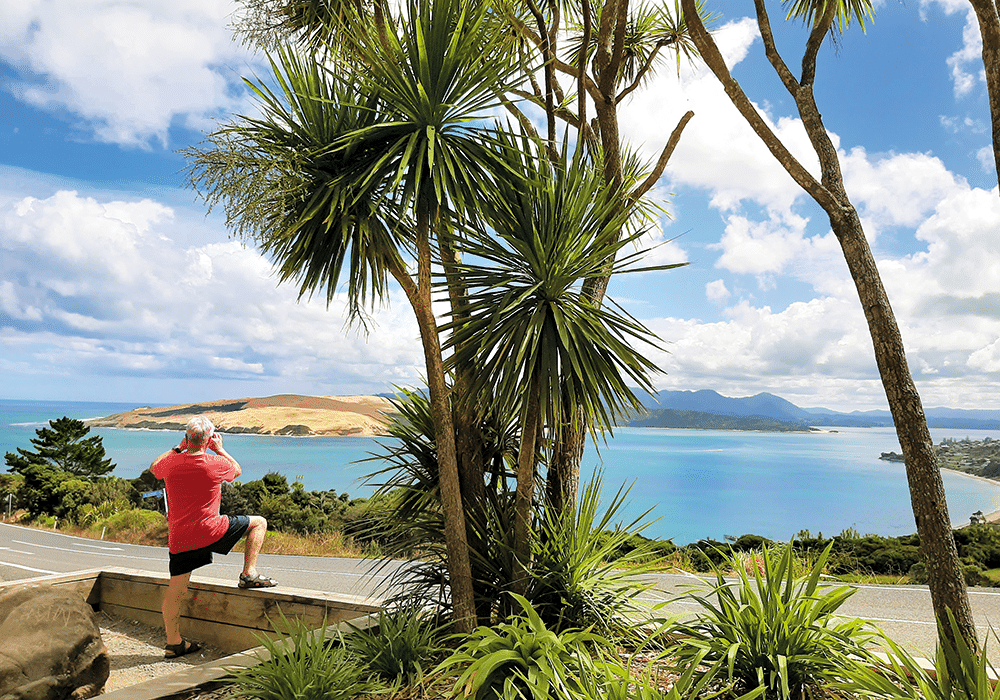

Leaving the forest behind, SH12 passes through farmland before dropping down to the entrance of the harbour. Huge sand dunes dominate the landscape on the far shore, while sandy bays curve around the southern side. The twin seaside settlements of Ōmāpere and Ōpononi stretch along the shores of the harbour here, offering opportunities for fishing, kayaking, boating and swimming.

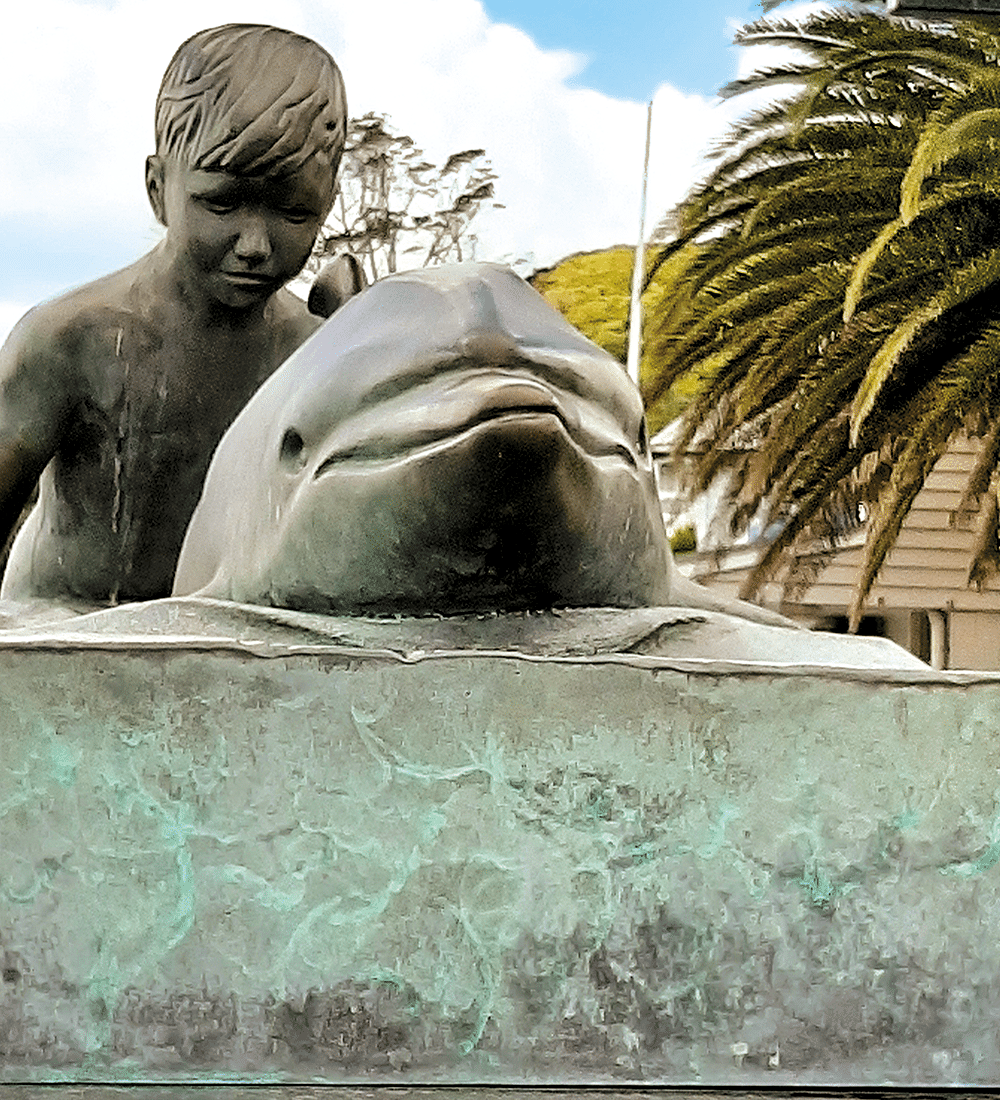

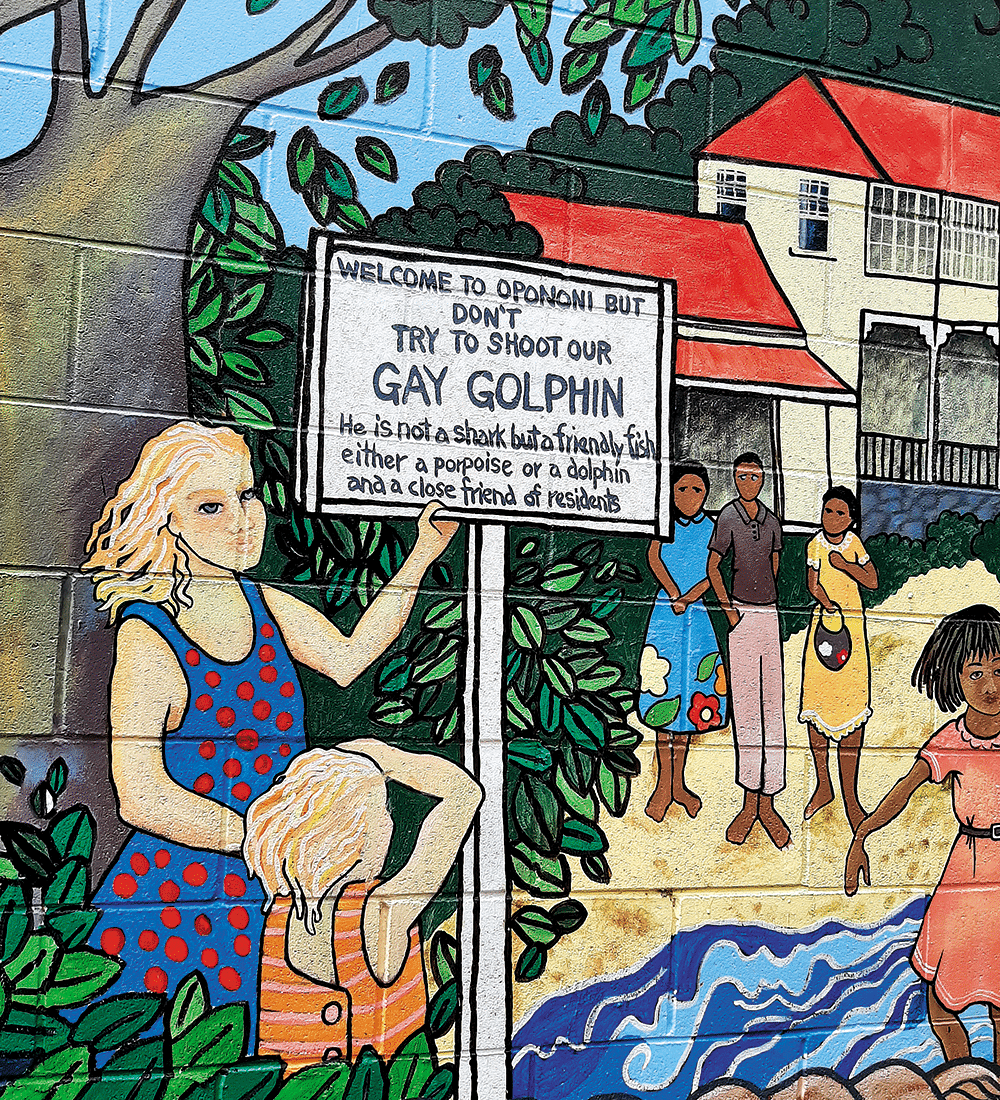

Ōpononi became famous in the mid-1950s when a bottlenose dolphin, dubbed Opo, began to play with swimmers at the beach. Unfortunately, Opo was found dead the day after she became protected by law, and was buried with full Māori rites beside the war memorial. There’s a bronze statue celebrating Opo, outside the Ōpononi Hotel.

Hokianga heritage

Rāwene is along one of the many headlands that jut into the harbour. The little town is New Zealand’s third oldest European settlement and was first known as Herd’s Point, after land was purchased by Captain James Herd. Timber mills and shipyards were established and in 1884 the town was renamed Rāwene. Although it was once a bustling centre, it’s a quiet spot now. There are galleries and cafes, some on piles over the water, and lots of picturesque old buildings.

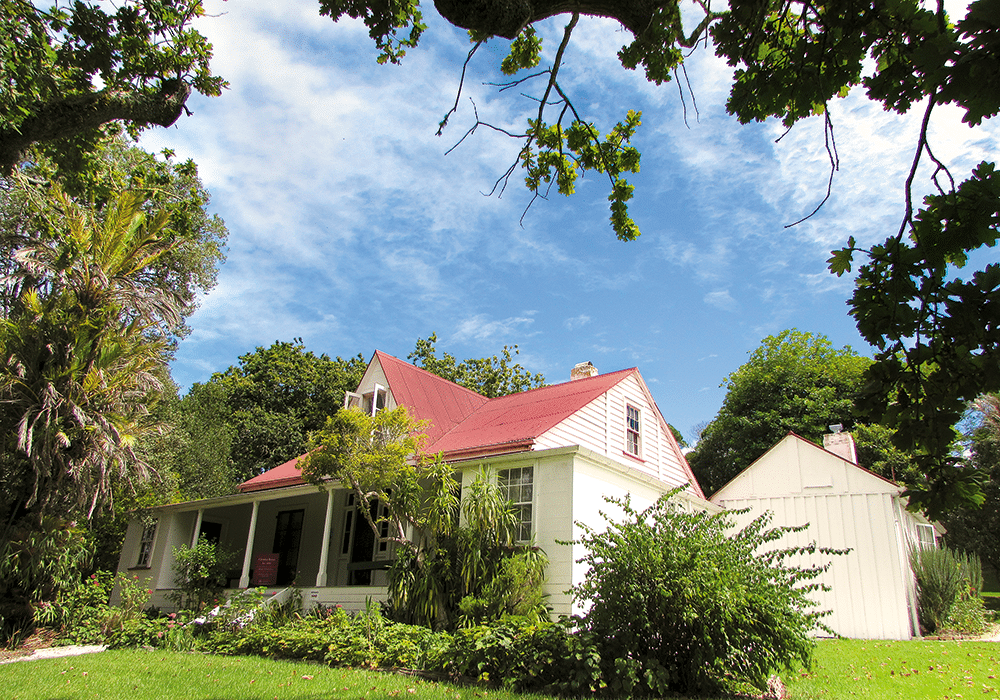

We were delighted to discover that one of these, Clendon House, was open to the public. This old homestead was built in the 1860s for James Reddy Clendon and his family. Clendon was one of New Zealand’s earliest settlers and had witnessed the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. He moved to Rāwene in 1861 as a magistrate and Commissioner of Customs, but his finances were poor. When he died in 1872 (aged 72) he left a young second wife, Jane Takatowai Cochrane, to bring up their eight children and pay off his debts. Clendon House stayed in the family until it was gifted to the Historic Places Trust in 1972.

What’s really fascinating about Clendon House is that all the furnishings and artefacts in the property belonged to the Clendon family: there’s James Clendon’s top hat and medicine chest, daughter Marion’s wedding gown, grandson Trevor’s military jacket. In the schoolroom the walls are papered with old newspapers (the earliest dated 1872), and maps and posters from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The family’s books, pictures, kitchen equipment and tableware are authentic. It’s like stepping back in time.

The North Hokianga

Time was in our thoughts too – we had a ferry to catch. To get to the northern side of the harbour, without taking a very long road journey, you have to go by boat. The Hokianga Vehicle Ferry is operated by Fullers and runs every hour. The crossing takes about 15 minutes and goes to the Narrows, near Kohukohu.

Kohukohu is another early European settlement. By 1830 the Hokianga Harbour was at the heart of New Zealand’s kauri industry. A timber mill was built in1879, and by 1906 there were 5000 men employed there. The end of the kauri saw Kohukohu decline as a settlement, especially after fires in 1922, 1954 and 1967 eventually destroyed the commercial heart of the town.

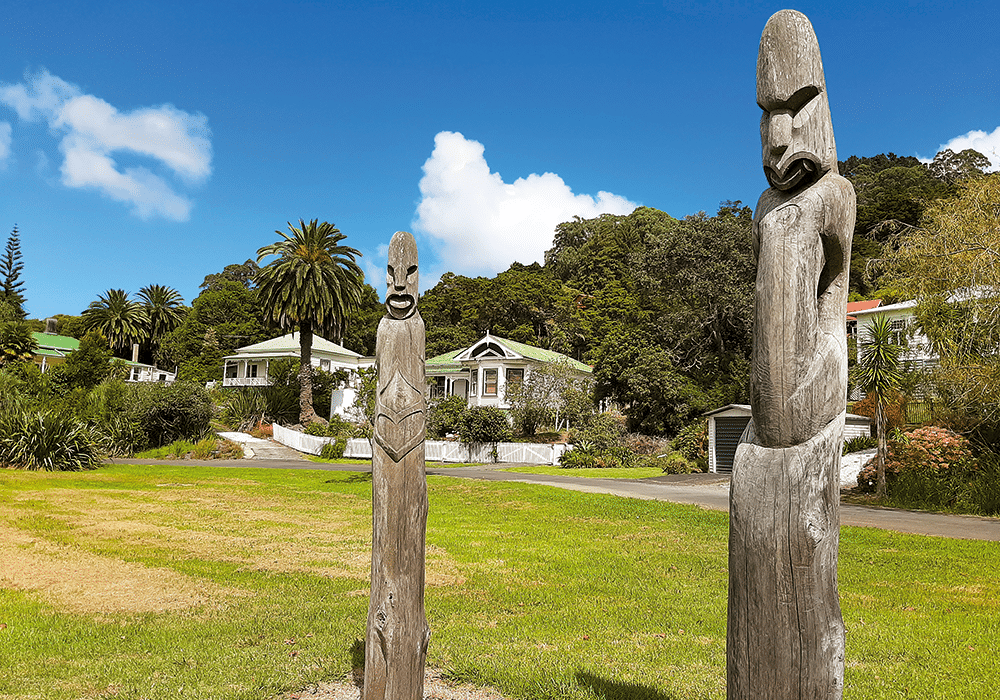

New Zealand’s oldest surviving stone bridge is in Kohukohu, built with sandstone used as ballast in ships coming from Australia. Visitors can discover the bridge and more than 30 other sites and buildings around the town. I’d picked up a Historic Village Walk brochure at the Hokianga i-Site in Ōpononi, and we checked out some of the pretty old houses near the waterfront and the surrounding streets, many built in the 1800s. Three pou nearby express the commitment of the local community to preserving the area’s cultural, political, historical and spiritual values.

Although it’s a small place, Kohukohu is home to many artists, writers and musicians. The town has several galleries, craft shops and cafes. The cafe beside the pub was freshly painted outside, Frida Kahlo style.

Off the beaten track

Exploring west from Kohukohu, we followed a winding road with stunning views of the surrounding mountain ranges. Coming down into Panguru, we saw the unmistakable, iconic image of Dame Whina Cooper. Born in Hokianga in 1895, she’s probably best known for leading the land march from the far north to Parliament in 1975. There’s a memorial to her with information panels, outside the Waipuna Marae.

The tar seal ran out at Pangaru and we followed the gravelled West Coast Road to tiny Mitimiti. As we neared the coast we passed paddocks full of horses, and the only other vehicle we saw had two horses tied behind. Then, at the road’s end, we came to a beautiful, isolated west coast beach. Although there were tyre tracks in the sand, the only other people we saw were two fishermen. It’s one of the most remote beaches in New Zealand and well worth the journey.

More Information

- There’s a holiday park at Rāwene and a motor camp at Kohukohu; also camping for NZMCA members in the area. There’s a campground by the visitor centre in the Waipoua Forest at 1 Waipoua River Road, but this was closed when we passed by.

- Hokianga i-SITE: 29 Hokianga Harbour Drive, Ōpononi.

- Clendon House hours: heritage.org.nz

- Waipoua Forest walks: doc.govt.nz