GENTLY PEACEFUL

For those who like dramatic vistas, solitude and stories from the past, the road colloquially known as Gentle Annie, from Taihape in the Rangitikei to Fernhill in Hawke’s Bay, is a compelling drive, writes Jill Malcolm.

The countryside near Spooner’s Hill, a few kilometres out of Taihape, looks deserted. And yet the road we embarked on, through the vast area of the North Island known as Inland Patea, is crammed with history. This contorted and often precipitous route, only 145 kilometres long, is not merely a link from one place to another but a destination that is best savoured in low gear.

Winter in a motorhome is always an adventure, and after a freezing 15 hours at the Gumtree Campground in Taihape, we checked out the road conditions and took a look at the town’s distinguishing gumboot sculpture.

Across the Hautapu River, the route follows a gorge before entering the broad Moawhango Valley. The change of landscape was abrupt, like the sudden silence when you step outside a crowded room and shut the door. Over the next two days, we saw only a handful of vehicles and one other human being.

The route follows an ancient Māori walking track across a huge tract of formidable high country stretching from the Moawhango River to the Heretaunga Plains, a mind-boggling distance on Shank’s pony, which made me thankful for modern transport.

The first European to venture into this rugged territory was a man of the cloth, the Reverend Taylor, in 1845, followed by the missionary William Colenso in 1847. Twenty years later, the Europeans, with their insatiable appetite for new pastures, began leasing or buying huge swathes of these high muscular hills to raise sheep for their lucrative wool. Some of the original sheep stations are still run by their descendants today.

The first settlers were brothers Azim and William Birch, who leased 46,850ha from Māori and established the highly productive Erewhon Station. By 1887, when wool was earning a pretty penny, they were shearing 60,000 sheep a year. No doubt this bought them riches but it also brought them troubles and a few years later the brothers fell out, never to be reconciled. Erewhon was split in two.

The first station we came across was at Moawhango, in the northern part of Rangatikei district and not far out of Taihape. Here we found the remnants of a once sizable village developed by Robert Batley in 1868, as part of his substantial farming enterprise. The store and post office he opened in 1882 still stands, but it’s definitely showing its age. Nearby was the old two-cell jail and on the grounds of the homestead, an elegant brick chapel displays a heart-wrenching memorial to Robert and Emily’s daughter Nellie who drowned in 1899 at Port Chalmers in Otago at the age of 21. Just four years later their 21-year-old son tragically also drowned, in the Moawhango River.

Today, the homestead comprises the lower storey of the extravagant two- storeyed house that Robert had built. Minus its top storey and modernised, there are few recognisable features of its original structure but the name on the new letterbox is still Batley. Down the road is the wooden Whitikaupeka Church, which was built shortly after the chapel to commemorate the area’s Māori tribal elders. It stands next to a marae and the old school buildings.

When we visited, Moawhango was so quiet as to be devoid of movement. A large bull glared at me from behind a flimsy fence and from somewhere near the woolshed an invisible dog barked a warning.

All along this route, unobtrusive signage indicates the vast sheep stations that define this part of the North Island. Among them you’ll find Oruamatua, Ohinewairua, Erewhon, Springvale, Black Hill, Mangaohane, Otupae, Ngamatea, Timihanga and Mangawhare. Much of the great sweeps of knotty pasturelands we passed were greenly carpeted and measled with sheep. The outbuildings, woolsheds and homesteads are often tucked away in the folds of the hills and hidden by swathes of exotic trees. When visible, they are diminished by the immensity of the landscape.

We climbed to Windy Point, which afforded a view of the Moawhango Gorge and the Kaimanawa Ranges, and revealed a vast, austere landscape that plunged into dark forested gullies, and soared to form a rugged outline against the sky. There was not a breath of wind. I read that during the road construction a fossilised whale’s head was found nearby, carried in marine sediment as these lofty peaks were thrust up from the sea. This was so many aeons ago it’s almost too big a gap to be grasped by the imagination.

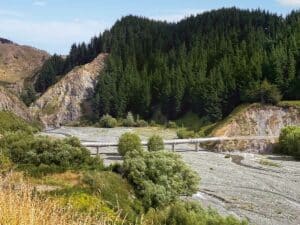

The road dived downwards from this pinnacle to a rough picnic spot by the historic Springvale Suspension Bridge over the Rangitikei River. In the early 1900s, life in these remote hills was made even more precarious by the fickle behaviour of the rivers and the bridge was built because farmers needed to transport their huge wool harvests to Napier Port by horse and cart. The old bridge, preserved as a rare example of its construction, was superseded in 1970. We lunched next to the riffling river and watched two harriers cruising above us on the thermals.

After lunch we hauled even higher up a long hill named by pre-European Māori as Taumatakerikiore, a name which refers to ‘digging for rats’. It seemed a long walk to find such delicacies. At the summit, 960 metres above sea level, we reached the route’s highest point and the watershed where streams changed direction and flowed to the east.

Before our camp for the night, we had still to drive Gentle Annie itself, the titanic hill that gives the route its name. There is nothing gentle about Annie. The ascent that began at the aptly named ‘Long Swamp’ was a winding skyward haul, and the descent was brutal. We engaged second gear and crept giddily down Annie’s flanks to safer levels in the deep valley of the Ngaruroro River.

On the river’s edge and divided from the world by looming bluffs is the extensive Kuripapango DOC camp, a secluded and sheltered campsite on the edge of the Kaweka Forest Park, and crowded with kanuka forest. In Māori, Kuripapango means ‘spotty dog’, but we were greeted by ersatz wildlife in the form of a mottled chook, who adopted us as her saviours as soon as we pulled up. We called her Henny and she never left our sides. If we went for a walk, Henny came too. She raced to greet us every time we climbed out of the motorhome, roosted under the chassis at night and was the first thing we saw peering up at us in the morning. It was, of course, cupboard love.

This was also the place we saw our first homo sapiens on our journey, when a burly Māori man emerged from the bush by the river. “Y’got the place to yourselves,” he said, with a grin wide enough to light up the valley. “ Well, we were just deciding whether that is good fortune or a bit dodgy,” we replied cautiously. “Nah,” he replied cheerily. “You’ll be right. It’s far too remote out here for anyone to bother you. I’m Tama by the way.”

A bit further up the road is Robson Lodge, an old farmhouse used for outdoor adventurers. Tama told us that, along with some other helpers, he had brought a group of troubled kids there from Napier. “The idea,” Tama explained, “is to show them that there is an alternative to a wayward life in the city. It’s tough up here. They cook on open fires, swim in the freezing river, and walk through the rugged bush and I tell them, ‘If you can survive this, you can survive anything’. Hopefully, some will make better choices after this experience.”

It is hard to imagine that around 1882, there were also two hotels in this area. The grand, two-storeyed Kuripapango Hotel was advertised as a health resort. Napier’s well-to-do, who sought to get away from it all, travelled the 42 kilometres from Napier by horse or carriage. The venture collapsed when in 1901, the hotel burnt to the ground and guests had to be ignominiously transported back to town in their night apparel.

Today the solitude is immense, the only sound the hiccoughing gurgle of the river. Overnight a cold dew made a sheen on the mossy grasses. In the cold early morning, the sky lightened to a pale blue before an orange sun rose above the peaks reflecting in the motorhome’s windows as if they were on fire. I was sorry to leave this peaceful place. Henny may well have been sorry to see us go. I threw her half a loaf of bread, which she fell upon with inelegant haste.

This Napier/Taihape Road dissects the great spread of Kaweka Forest Park, and the route then winds through dark exotic trees. We drove at our own pace until we came to Blowhard Bush Reserve, a nurtured 65-hectare remnant of podocarp forest where native birds abound. I walked through the trees serenaded by three bellbirds and accompanied by fantails and one North Island robin.

The route had already crossed the border between Rangitikei and Hawke’s Bay and at a high point, the great sweep of the Heretaunga Plains spread into the distance in a panorama so far-reaching I could just make out the white line marking the cliffs of Cape Kidnappers. Now in Bay country, it was obvious we had left Gentle Annie behind and for me, the drive ended at a white headstone I found on the side of the road near Omahu, just short of Fernhill. Its title was fitting:

“THE FINISH: In memory of Patriarch, one of the handsomest gamest and most docile of equine celebrities who died on Sunday 17 Sept. 1894 aged 25 years. This table is erected by Campbell, the old man of Ngapuke” It was a poetic ending to an epic highway.

Read more stories in this area here: