A powerful message emanates from the huge mural on the side of the expansive wall of Napier’s MTG building in Browning Street.

The subject is a surreal depiction of three children on top of a dead and disintegrating whale. One is collecting paper rubbish, spearing it on a stick.

Another is drawing windows on what looks like a cardboard house, and a small girl, crouched on the whale’s fin, is scooping oil from the surface of the sea with a saucepan.

The expression on their faces is bewilderment tinged with hope. This complex, imaginative mural is the work of the acclaimed Russian artist Rustam Qbic, and without exactly understanding why, it has haunted me ever since I saw it.

In fact, I didn’t just see it, I was mesmerised by its meaning: “Clean up our seas.”

Taking oceans to the streets

The work is one of 53 that now adorn public walls in Napier and Ahuriri that emphasise the same theme.

They are not intended to plunge their observers into gloom for the future but to highlight the plight of our polluted oceans and bring the beauty of its fishy inhabitants into public gaze. Some images portray a ray of hope.

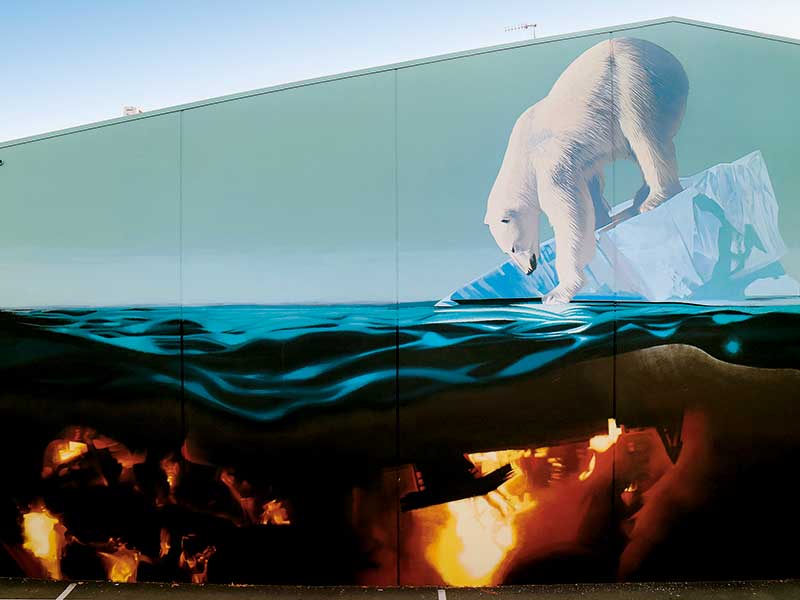

Among the 53, a polar bear stands on a diminishing iceberg, ghostly penguins walk a road now bulldozed by heavy machinery, and a whale carries a boat on its back and is surrounded by everyday human detritus.

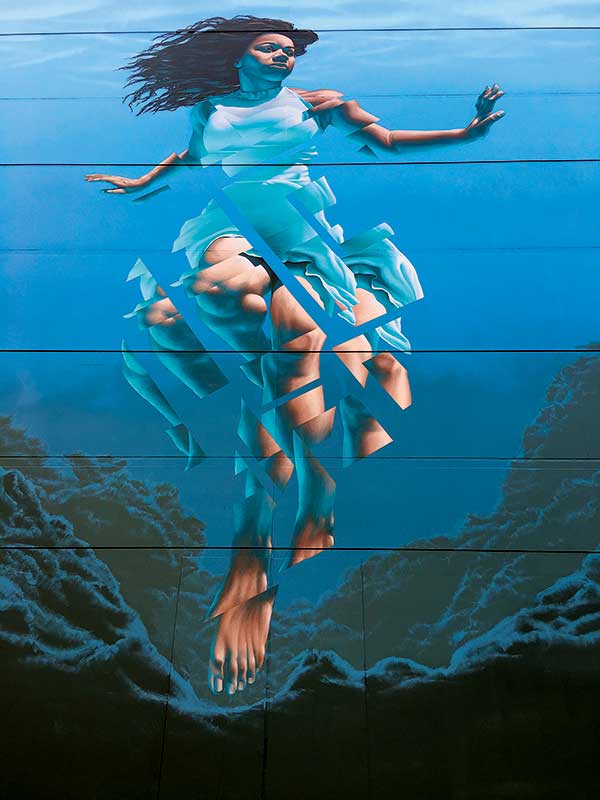

Another huge whale has a transparent skin revealing the litter that is scattered through its body. In a statement on global warming, a young girl is immersed in rising water. She looks resigned to, rather than terrified of, her watery grave.

And I came across a wonderfully lyrical work on the expansive wall of Raffles Street, downtown Napier, by Hawke’s Bay painter, Freeman White. It depicts a diver filming a majestic shark and is a tribute to the late Sharkwater film-maker Rob Stewart, who recently drowned while filming in America.

Environmental change through art

It was sharks that brought about this powerful worldwide crusade, in which Napier has become a significant player.

The movement comes under the banner of a foundation called PangeaSeed that was formed by Hawaiian-based American wildlife photographer Tre’ Packard.

I am not sure what the ‘Pangea’ stands for, but ‘Seed’ is an acronym for sustainability, education, ecology, and design.

The foundation fosters more than the artworks, incorporating discussions, teaching, activities, exhibitions, research, and action. And according to Cinzah Merkens, co-ordinator for the two Napier festivals in 2016 and 2017, the messages of awareness of ocean creatures and conservation of the seas are gaining momentum.

PangeaSeed’s beginnings

Like many great ideas, PangeaSeed began simply. In 2009, Tre’ Packard began covertly photographing sharks to bring to notice the appalling practice and illegal trading of shark finning. His findings shocked him.

Hoping to draw attention to the issue, he organised an exhibition in Japan, called Sink or Swim, which showcased his work and those of other like-minded artists. Cinzah Merkens was invited to contribute.

The event provoked much attention and was encouragement for another exhibition, which was shown in several places along the west coast of North America.

Awareness of the brutal treatment dished out to the creatures of the deep began to take hold. One of the exhibitors and exhibition curators was a friend of Tre’s, a New Zealand artist teaching in Sri Lanka, Aaron Glasson.

Back in Sri Lanka, it was Aaron who executed the first ‘sea walls’ mural, which centred on the unethical practice of manta ray fishing for their raker gills.

The attention this received led to the first festival of mural artists who were painting with a purpose, which was held in Mexico in 2014, when 15 artists from around the world were invited to adorn the walls of Isla Mujeres with suffering seas as the topic.

“The 15 murals that resulted from this event went viral,” Cinzah says. Since then, Tre’ Packard’s foundation has organised and curated 12 non-profit ‘Sea Walls: Artists for Oceans’ programmes around the world in collaboration with a growing network of 250 artists.

Aaron, who now lives in the United States, is PangeaSeed’s creative director.

Sea Walls: Artists for Oceans Festival

The first New Zealand event was held in March 2016. With Tre’s encouragement, Cinzah had pitched the idea to Napier City Council of the Art Deco city becoming a host for one of the now worldwide mural festivals.

Not only was the council open to the idea but it also came up with half the budget to sponsor travel and accommodation for 30 local and international artists who volunteered their skills.

Tre’ Packard came to New Zealand to help set up the project, and at the end of the 10-day festival, large-scale murals adorned the hitherto blank walls of Napier and Ahuriri.

The event won such accolade that a second ‘Sea Walls: Artists for Oceans Festival’ was held in Napier in March this year.

Of the 23 artists invited to contribute, 10 were international, coming from North America, Spain, Russia, Australia, Germany, and Switzerland. Now there are 53 murals in the Napier area. Around the world, there are 300.

“In New Zealand, the feedback has been amazing,” Cinzah says. “The idea is to shine a light on the subject and create hope for improvement at the same time.

“What’s going on in our seas is an eye-opener for a lot of people. Many are shocked to know that shark finning is happening on their doorstep, for instance, right here in New Zealand. And that’s only one of the cruel, morally wrong practices that is destroying the planet’s sea life.”

It was certainly an eye-opener for me. Not so much grappling with the issues—I knew the oceans were in trouble—but the murals that make up Napier’s open-air gallery are spectacular.

I spent two happy days wandering the streets of Ahuriri and Napier.

The iSite has location map of all 53 murals but I preferred a voyage of discovery, surprising myself as I came across mural after mural, most of which were colourful, captivating, and massive in proportion.

I undoubtedly missed quite a few and that will have me coming back to discover more each time I am in the area. And it wasn’t just the images that excited me.

In those acts of creation lies a change of attitude that points the way to a more optimistic future