|

|

Welcome!!

|

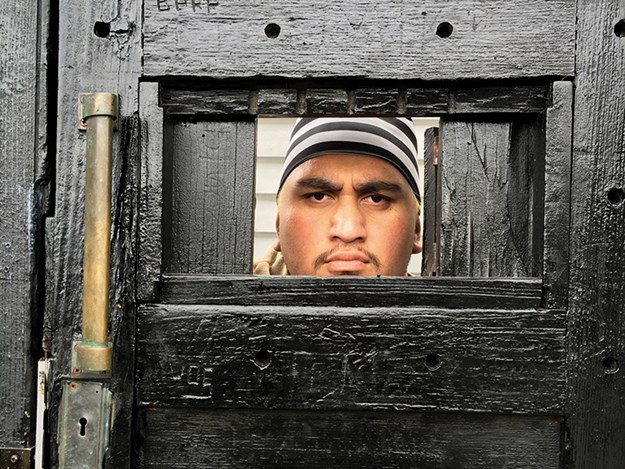

When justice was ruthless and punishment unspeakably cruel, terrible things happened in the Napier Prison on Bluff Hill. Built in 1862, it is the oldest prison in New Zealand still standing. The dens of iniquity were decommissioned in 1993 and left deserted until 2002, when in a bold move, Marion and Toro Waaka leased the complex, tidied up the chaos, and turned it into the tourist attraction open to ‘voluntary’ visitors who pay for the privilege. Even so, walking up the steps, ringing the bell and announcing my arrival through a slit in the imposing black door invoked a degree of trepidation.

The oppressive buildings are made up of dreary concrete walls, grills, wire enclosures and dismal interiors. Although there are illustrations and explanations pinned to various walls, it has been left more or less as it was. There are no theatrical enhancements or re-creations, and the authenticity better feeds the imaginings.

|

|

Napier Prison’s stone walls were quarried from what are now the Centennial Gardens across the road

|

In addition to its primary function, which was the incarceration of criminals, the prison was also used as a psychiatric unit (referred to in those days as a lunatic asylum), an orphanage, an alcoholics’ lockup and a borstal.

I had heard of the Napier Prison tour through an informant who told me it was curious and fun, which I thought was an odd choice of words for one of the grimmest places in the country. There was little fun to be had for the inmates. In the early days, they were forbidden to sing, swear or shout and denied any form of amusement. Transgressions of these rules were punished by solitary confinement in The Pound. If you weren’t mad before being incarcerated for 23 hours a day in one of those awful windowless cells, you soon would be. The Pound was named for the amount of money relatives had to pay to release a family member and return him/her to a regular prison cell.

|

|

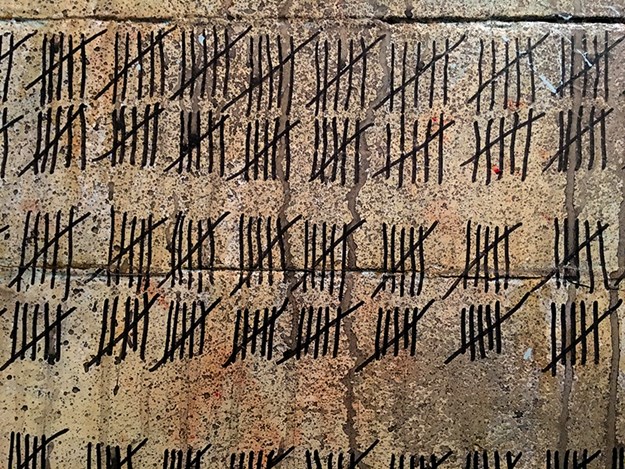

Prisoner graffiti, counting the days

|

Pinned to a wall in one of The Pound cells is a blurry photograph taken of Hauhau prisoners awaiting deportation to the Chatham Islands in 1866. Depicted among them was possibly the most famous, the Mãori leader Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki, who fought with government troops against the Hauhau cult and yet was accused of spying. He was pardoned in 1883, and although he spread messages of peace, he also continued claiming back land that had been confiscated by Pakeha.

Another Maori leader, Kereopa Te Rau, was wrongly convicted of murdering the missionary, Carl Volkner, and swallowing his eyes. He was incarcerated at Napier, hanged in 1872 and granted a pardon in 2014, which was a bit late to do him any good. His photograph, taken a short time before his death, depicts a man of noble features and sad, defeated eyes.

Hangings took place at the back of the jail by employing kitset gallows. The hanging judge, along with the infamous hangman Tom Long, travelled the country like a small circus. Spectators paid a shilling to view the grizzly events.

|

|

The hanging yard

|

The most popular hanging at Napier was that of Rowland Edwards in 1884. He had cut the throats of his wife and four children after a premonition that they were about to be consumed by fire. Those who had not bought tickets to the show climbed trees outside the wall to get a good view.

Rowland’s grave, surrounded by a picket fence, is in the courtyard where he was hanged. More recently the prison housed some notorious criminals such as the murderous Terry Clark (aka Mr Big, head honcho of the Mr Asia Drug Syndicate), and others not so notorious such as gang members, predominantly from the Mongrel Mob. Interestingly the mob’s name came about in the 1960s when, in nearby Hastings, youths from local welfare homes were on trial. The judge called the group “a pack of mongrels” and unwittingly passed to them a title that stuck. The Mongrel Mob became the biggest gang in New Zealand.

Back in the cell-blocks I peered through the clanging iron doors into the imagined horror of life behind bars and recoiled from the cramped, damp, and gloomy atmosphere. In the cells, high grilled slits served as windows, and let in just enough light for me to decipher some of the messages scribbled on bed boards by hapless jailbirds. Few were cheerful or held any hint of hope.

|

|

The Garden of Redemption

|

I found one bright corner of the prison comprising a small garden of coloured tiles and statues. It was created by 10 high-risk teenagers who a few years ago were given a second chance by staying in the prison for a month and undergoing a rehabilitation programme that was filmed for a TV documentary called Redemption Hill. Although the experiment was partially successful, a poignant aspect was added to the garden’s small expression of hope by a plaque acknowledging two participants who had later died.

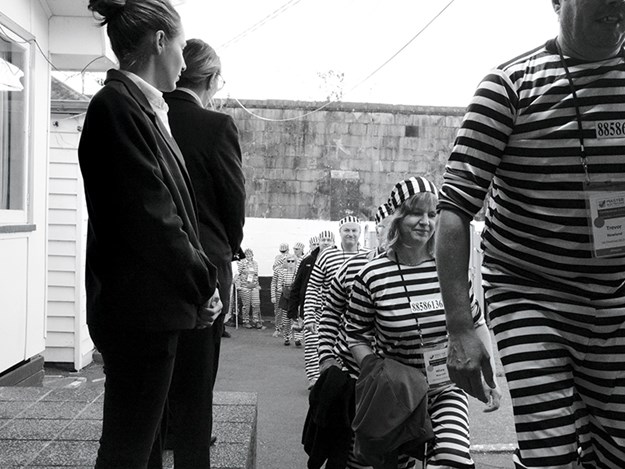

I also discovered that my informant had been right. Nowadays there is fun to be had at the prison. Four cells have been set up as ‘escape rooms’. Enter one of these and try to find your way out through puzzles, questions and by following storylines. In one cell a ‘prisoner’ is handcuffed and blindfolded and (under supervision) given an hour to work out how to make their escape.

|

|

‘Prisoners’ on the way to The Escape Rooms

|

“These games are really popular,” said Marion. “Many people come back for more. Interestingly, so do quite a few people who once served time here, even though their memories would hardly be about fun.”

It is said that the earliest inmates who died here were buried upright in the graveyard so their souls could never rest. Ghosts are alleged to roam within the prison walls. Apparently, there was no escape even in death. Anyone who enjoys spine-chilling tales can take the ghost tour.

My own escape an hour after I’d been detained was unhindered. I stepped through the door where so many people and their stories had come and gone and, taking a deep breath, I embraced my freedom.

Self-guided tours, pre-book ghost tours, and Escape Room experiences are available every day. Note, it is best to park your RV elsewhere as the driveway is steep and there is little on-site parking.

Find motorhomes, caravans and RVs for sale in NZ