Paul Owen takes a whole different type of track when he boards the train to cross the South Island from Christchurch to Greymouth.

Paul Theroux, the American travel writer and novelist, made his mark by writing about journeys by train, and once remarked that “the worst trains take one across the best landscapes”. Obviously, Theroux never travelled on the TranzAlpine Express, which crosses the South Island at its narrowest point between Christchurch and Greymouth.

If he had, he might have felt compelled to make an exception to his best-travel-by-worst-train maxim. For in the case of this engaging excursion across the Alpine Fault that dramatically uplifted all the surrounding mountains, ‘one of the best trains takes one across the best landscape’. You know that this train is special as soon as you enter the Christchurch terminal for the Express, a building comparable to any airline terminal, and get greeted by the same friendly smiling folk who will be your hosts once aboard the train. Here, you can check in heavier luggage for consignment to the train’s goods carriage, including bicycles if you’ve previously confirmed that there is space for them. Then you find your seat aboard the train, and quickly realise that the view from it will be far more panoramic than you expected. The carriages have huge windows that range all the way from elbow level to well above your head, and you’ll feel more like a part of the scenery you’re passing through rather than separated from it. The last time air travellers enjoyed such a visual connection with the country they were travelling past they were on board a dirigible.

Then, there’s that ultimate luxury – space. The Express offers two classes of seat, one with seats facing a central table, and the other with plane-like seating and fold down tables. The former costs $229 for the full four-hour journey between the two coasts, while the other is $50 less at $179 (add an extra $40 to each for peak prices). Yet even the ‘cheap’ seats offer the sort of leg room that an airline would reserve for business passengers and are served by fold-down footrests. There’s no opportunity to fold the seats into beds, but nor is this inducement for sleep required, for there’s plenty to see once the journey begins, and the provided headphones give access to a lively commentary full of humour, history, geology, and info about the passing flora and fauna. There’s even the odd ghoststory to tune into. So, sitting comfortably? Let’s go!

Christchurch to Darfield

The train pulls out precisely on time at 8.15am and the 224km trip begins. If you’re of a certain age, you might be feeling the sort of excitement you felt as a child at this point, back in the days when hundreds of passenger trains and railcars connected all of NZ’s main centres and towns. As someone who can recall riding into Auckland with his grandad on a train hauled by a steam engine, just the slight yet enjoyable swaying motion of the Express and the rhythmic clicking of the rail joins instantly brought it all back.

We soon leave the graffiti-decorated concrete walls that line the tracks in suburban Christchurch behind, and begin whizzing across the open plains of Canterbury, the train moving at a speed far above that of a canter. We rail through many road crossings and receive the waves and smiles of waiting motorists and their families, all of whom appear to be overjoyed that it’s a passenger train that they’ve had to halt their journey for rather one of KiwiRail’s freight runs. It’s the first of many such friendly interactions between the train and adjacent road users and other observer of the Express’s crossing of the plains. Milk tanker drivers toot, motorcyclists wave, and kids playing in backyard lots pause their games to stand and wonder at the power of the twin DXC diesel-electric locomotives as they collectively develop 6600 horsepower and shake the earth beneath their feet.

Rolleston is the first of four stops in the journey of the TranzAlpine Express, and cheaper fares than the full journey also await those who either join or depart the train at Darfield, Arthur’s Pass, or Moana (on Lake Brunner) stations. The Express travels from Christchurch to Greymouth in the morning, then returns the same afternoon, reaching Christchurch at 18.31pm. You can therefore use it to arrive at the high point of Arthur’s Pass from Christchurch at 10.52, enjoy five hours of exploring the natural beauty of the Arthur’s Pass National Park, then catch the return train back to Christchurch, arriving at 16.38pm. Lake Brunner, with its opportunities for fishing and tramping, would also make Moana another attractive stop-over station. It sure beats having an air steward hand you a parachute midflight and ushering you towards the door.

Darfield, the town 35km west of Christchurch is the next stop. It’s famous for the arch-like zephyr clouds that form above it when the afternoon breeze blows – something for travelers on the return journey to watch out for.

Darfield – Arthur’s Pass

Upon leaving Darfield the pace of the train slows as the Express begins its climb towards the pass that bears the name of Arthur Dobson, the man tasked with finding a viable route between the West Coast and Canterbury. Dobson was tipped off by a Māori chief, Tarapuhi, that a pass existed that connected the watershed of the Waimakariri River with that of the Otira River on the western side of the mountains. When Dobson’s brother, George, surveyed the pass and two other alternatives and reported that ‘Arthur’s Pass was the most suitable link between Canterbury and the West Coast’, the name stuck.

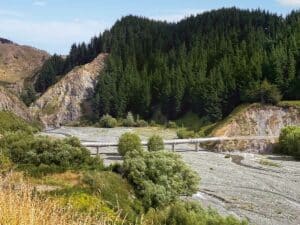

The engineering challenges posed by establishing road and rail links between the Waimakariri and Otira watersheds were huge, something that quickly becomes evident as the train snakes its way through the gorge of the former. You cross bridges and viaducts that literally take your breath away, the Express suddenly suspended 70 metres in the air above narrow canyons with vertical walls, with only 100-year-old steel and concrete constructions resisting its tumble towards destruction. Meanwhile, the scenes from the right side of the train towards the turquoise Waimakariri as it froths and foams its way towards the braided channels of the plains are total eye candy. It’s a great part of the journey to savour from the open carriage, where windows won’t muddy the views with their reflections. The gorge is soon conquered, and the train bursts out into the wider glaciate valley of the upper Waimakariri after passing through the little settlement of Cass, with its tiny station made famous by an iconic painting by Rita Angus. Blink and you’ll miss it as the train travels quite quickly at this point, much to the chagrin of devotees of the artist. Still, it’s nice that KiwiRail keep the little-used station in good nick with regular coats of similar colours as used by Angus when she did the work back in 1936.

Arthur’s Pass – Moana

It takes two and a half hours to reach the highest part of the journey – Arthur’s Pass station, 737 metres above sea level. There’s a stop of around 20 minutes so that extra locomotives can be added to the train to help slow our descent through the steep decline of the 8.5km Otira tunnel. They’ll be decoupled later at Otira station, ready to help haul the return train. The difference between the heights of the two railheads at either side of the tunnel slowed its construction, as did the tough weather conditions and poor accommodation of the workers, who regularly went on strike for better conditions (eight were killed during the tunnel’s construction). It took 15 years to link the two railheads, and the tunnel finally opened in 1923, the timing happily coinciding with the introduction of electric traction locomotives. A coal-fired power station at Otira supplied power for the electric locomotives to haul trains through the tunnel until 1977, which meant the carbon monoxide produced was released to the open sky instead of nearly asphyxiating passengers though the use of steam locomotives in the tunnel. Access to the open viewing carriage is closed when the Express is in the tunnel, especially as the number of diesel-electric locomotives now hooked to the train has doubled.

The train exits the western side of the tunnel to a noticeable change in climate and vegetation; the dry scrub/pine plantations of Canterbury suddenly replaced by stands of the native rainforest and the rich lush pastures of Westland. The native podocarps dominate the views, with some Kahikatea reaching 60 metres in height, enough to close out glimpses of Mount Murchison (3299m) at times. Not that I’m complaining, they’re New Zealand’s equivalent to a North American Redwood or Sequoia, and at this height, they’re over 1000 years old. Go you good trees!

Moana – Greymouth

Lake Brunner is called Moana Kōtuku by Māori, a reference to the way the white heron once populated the lake before nearly being hunted to extinction. Even back then, a popular Māori whakatauki or proverb was “He kōtuku rerenga tahi” highlighting that a kōtuku’s flight is seen but once in one’s lifetime. In that case I’ve been extremely lucky, however there were none present during our stop on the lake’s front. Maybe next time…

Moving on, the train travels through the untouched rainforest of the Arnold Valley, full of large specimens of the three native ‘pine’ trees – there’s ‘silver pine’ (South Island beech), ‘red pine’ (rimu) and ‘white pine’ (kahikatea) all casting their shadows over an area of vegetation so dense that it looks like tropical jungle.

By contrast, the Grey River valley carries all the scars of history. Dobson was named after Arthur’s Pass confirmer, George, after he was murdered by the Burgess Gang (later hanged in Nelson for other equally heinous crimes) two years after his survey of the passes. There’s a glimpse of the Brunner mine disaster memorial, before we squeeze through the gap the river carved into the hills and into Greymouth, a town fortuitously positioned to be a great starting point for any further exploration of the wild and wonderous West Coast. This trip is rightly labelled one of the world’s great train journeys. Paul Theroux would love it.