The first time I saw an RV rally was at the infamous Nambassa Festival in Waihi. From then on I yearned for a home on the road. It was 1979, and in New Zealand the hippie counter culture was still in vogue. At Nambassa I found exuberance, rebellion and freedom, an irresistible mix for someone brought up to worship the gods of respectability and cleanliness. At that time, motorhomes were nearly all old vans or house trucks with various degrees of enhancement.

That image of Waihi was laminated in my mind until last month, 36 years later and the first time I’d stayed in Waihi since.

After the flatness of the Hauraki Plains, the high cliffs of the Karangahake Gorge, was like a welcoming handshake. Although eight kilometres away it has a strong link to Waihi township. Gold is the glue.

In 1878 two prospectors, John McCombie and Robert Lee, struck gold on Martha Hill in Waihi and from their find developed one of the most significant gold and silver mines in the world. More gold was found on Karangahake Mountain and soon a network of railways, shafts and tunnels defiled the natural beauty of the gorge and multiple stamping batteries destroyed its peace.

Since the mines closed in 1950, tranquility has returned. At the entrance to the gorge, a large car park is the starting point for two walking tracks through the old mining trails. The Tunnel and the Windows walks are both thinly strewn with mining detritus. The former, runs along a ledge on the banks of the Ohinemuri River and, not surprisingly, through a tunnel that is one kilometre long and has recently been installed with lights.

I spent more time on the Windows Walk, which followed a railway track through low bush. It included a steep climb and several dark, damp tunnels.

I’d forgotten to take a torch and my cellphone was a poor substitute. I think I stepped in every one of the puddles that littered the ground. Gaps in the rock (the windows) allowed spectacular views of forested cliffs and the river far below.

I was in need of sustenance after these treks, which led me to the historic Waikino Railway Station further along the gorge road. An excursion train from Waihi comes to a halt here and passengers find refreshments in the café, which is furnished as it might have been in the early 1900s.

The old building was transplanted from Paeroa. The atmosphere was charming and cosy and quite unexpected. Railway and gold mining memorabilia cover the walls, a fire burned in the old brick fireplace, the tables are laid with lace table cloths and food is made in the kitchen (aka The Engine Room). I couldn’t decide between the kumara and blue cheese soup or the bacon and egg pie. In the end I decided I needed both.

Above the fireplace hangs a large photograph of the Victoria Battery, once the largest quartz crushing/gold extraction plant in the Australasia. Residue and reminders of this giant complex are in a reserve just across the road from the station and that’s where I headed to next.

The Battery (circa 1897), once a massive complex, now looks as if some giant has thrown all his toys out of the cot and left them to rust. I didn’t think I’d find the place riveting, but then I met two volunteers from the Victoria Battery Tramway Society; Mike Harding and George Capper.

Old mining methods fascinate these men. In a bright yellow mini train, Mike toured me through the giant debris on a purpose built rail track. His enthusiasm transformed the wrecks into a vision of the ore-filled wagons being winched up the incline to dump their colossal rocks, and of all the huge-scale, time-consuming processes that extracted the glittering prizes. We passed old lifts, bits of grinding wheels, crushers and stampers and, most dramatically, a honeycomb of concrete bases that once supported towering cyanide tanks.

The images of the men who struggled to make a living in such a demanding environment filled me with a different kind of awe. They were tough, resilient, and sometimes so desperate to pay off debt that they cut off their thumbs to get worker’s compensation.

In the Waihi Museum (also worth a visit) some of these dismembered digits are on display, preserved in jars.

The only building left standing once housed a large transformer that replaced water-generated power. Electricity came down the lines from the Waikato River’s Horahora Dam, which is now submerged beneath Lake Karapiro.

The transformer building is now a museum complete with one working stamper. With one stamp George demonstrated the level of noise that emanated from these giant crushing machines. Just one thump was a gorilla assault on the ears and there were 200

of those monsters working non-stop night and day. The noise was literally deafening for hundreds of men. The pounding could be heard in Paeroa and Waihi and the story goes that Waikino residents became so used to the noise they found it hard to sleep when it was silenced on Sundays.

I was gold-struck and yet there is more to Waihi than the mining. Residents have made much of the town. Decorative lamps and colourful banners light the main street, bronze statues and murals depict the past. There are 21 eateries, the roundabouts are decorated with steel balls used in the ore-crushing process, and the lovely old buildings – built in Waihi’s heyday – are painted and restored. Most notable of these are the Rob Roy Hotel, the old library and the Masonic Lodge.

But the building that dominates the town is the old Cornish Pumphouse on the lip of the Martha Mine pit. I’m sure the aesthetic was not a priority when it was built in 1903. Nonetheless, this striking structure is a monument of pleasing proportions.

Despite the many attractions of Waihi, not least the famous beaches nearby, I could not escape the gold.

To introduce visitors to an overview of Waihi’s past, the Gold Discovery Centre opened two years ago. I’m not one for spending much time in museums, but manager Eddie Morrow assured me that this centre was definitely not a museum.

“It’s an experience,” he said firmly. “Hands on, interactive and entertaining, as much as educational.”

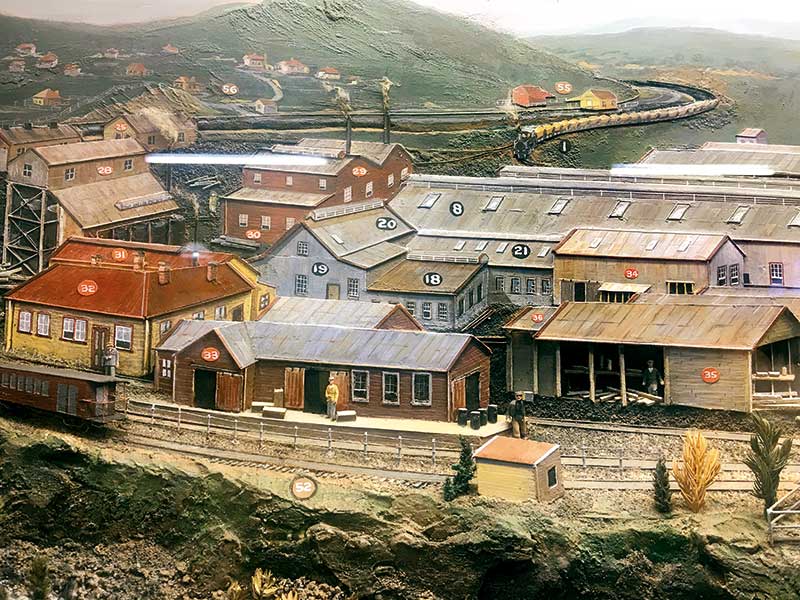

And so I found myself playing two-up with a tough ‘ghost’ miner and having my thumb cut off when I owed him money. I digitally designed my own gold jewellery and took a photograph of myself wearing it. I was chatted up by two hologram miners who taught me how to blow up rock and work a jackhammer. The working miniature models, storyboards and an abundance of displays were so engrossing I almost missed the bus for the goldmine tour.

Having spent time looking into the past, I was interested to see how the gold story continues today. The best way to do this was on of the regular tours that visit both the open caste Martha mine and the Correnso underground mine.

When Oceana Gold bought both in 2015, there had already been a small slip on the north wall of Martha’s mine. It was bad luck but not an unexpected event when at five in the morning, on the fifth of May 2016, two million tonnes of rock and rubble collapsed spectacularly into the pit. Some of the rocks were reportedly the size of houses. The mine is closed while the company figures out how to tackle the enormous task of clearing the rubble. The four-kilometre pit-rim walkway is still open for anyone who wants to view the yawning cavity from all angles.

The Correnso mine was in full swing. We were allowed on site but at a safe distance while Mike Legg, ex-school teacher and now tour guide, explained the mining and extracting process in detail. Oceana Gold takes safety seriously and it was a terrible thing that a week later a young miner, Tipiwai Stainton, met his death underground when his 50-tonne loader rolled. The Australian/Canadian company had been accident-free for the 25 years it had been operating in New Zealand.

Apart from safety, the company’s most impressive approach was the various plans to replace the environment that mining so deeply disturbs. One day in the future, when the gold has gone, the Martha Mine will be a lake, although I wouldn’t buy a boat just yet. Replanting of vegetation has already begun on the high, waste-rock embankments and despoiled terrain. Cyanide contaminated water is piped to a holding area where sunlight destroys the cyanide. It’s then fed into a large man-made lake. The rim of this is planted with reeds. The area is a bird sanctuary and the only inland breeding place for New Zealand dotterel.

Mike produced a nugget of gold, which he held out to us in the palm of his hand. And because we now understood the long, arduous labour that goes into the production of just one ounce, the five us on the tour gazed at it with reverence.

I was reminded of a prospector I once came across in the outback of Australia. He’d chosen a rough and lonely life hunting for the treasure, living in the back of his truck with a half-cut corrugated tank for shelter. I asked him what he would do with the money if ever he struck it rich. “It’s not the money, lady” he said. “It’s never been the money. I just want gold to hold in my hand.”