To clarify, I didn’t go to Great Barrier Island in a motorhome. I flew there, rented a house, stayed for three days, and used a hired car. But when I stop juggling a couple of day jobs, and retirement eventually happens, I will be back there, without hesitation, in a motorhome and I will stay for a month, maybe two.

For me, Great Barrier Island is the dream of paradise. It has stunning white beaches threaded between headlands on the east coast and quiet coves with bush down to still clear water on the west coast. There are over 100 kilometres of walking tracks through fine native bush, kakas cavorting in the trees, and wide views of Hauraki Gulf and the Pacific Ocean.

The natural beauty of the island is exceptional and to balance that, in a good way, the population of 800 seem to be friendly, laidback characters. The pubs, the social hub of the small island communities, know how to lay on a good night, especially on Friday and Saturday, for locals and visitors alike.

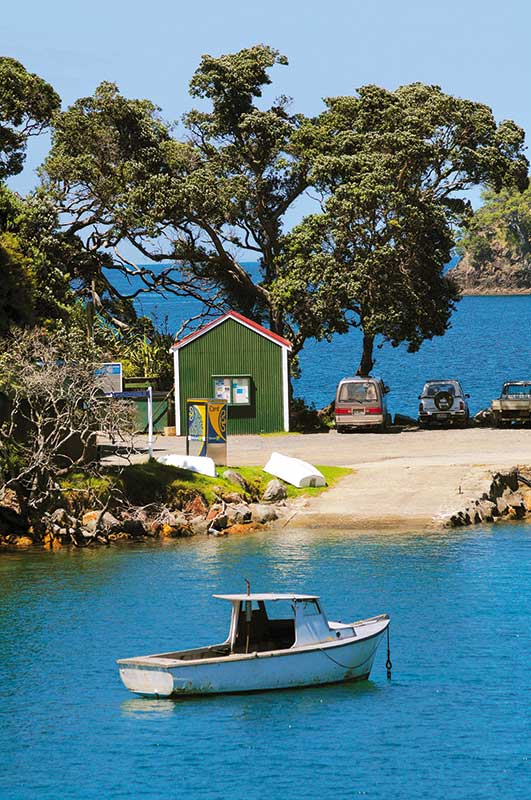

The island is, as the kaka flies, 35 kilometres long and half that at its widest. Its mountainous topography makes it seem a bigger and the steep, winding roads make driving a few kilometres feel like a longer journey. In the middle, Mount Hobson’s egg-shaped topknot dominates. At 621 metres, it’s a modest mountain but on the west side, from Port Fitzroy, it rises pyramid-like from the sea.

The easier approach is from the east, at Windy Canyon, so this is the route we choose. We arrive, with friends, on the first flight of the morning, sort the hire car and head directly for the Mountt Hobson track to do this walk before the heat sets in.

For the first hour we plod through an ancient volcanic landscape with phallus-like rocks standing stark and tall, dark drippy chasms, cliffs fluted like organ pipes and razor ridges. The forest is second growth indigenous, gnarled and hardy, beaten into submission by wind. This area was extensively logged for kauri between 1925 and 1941 and we pass sturdy weathered derricks that once hauled logs up ridges and swung them over into other valleys.

The track steepens and the bush thickens until it’s virgin – too steep for the loggers – and we notice birds again, the little birds, fantails, tomtits and families of fluttery grey warblers. There are tuis, kereru and kaka too, flying high and squawking loudly over their territory.

The final 15-minute climb is on smart wooden steps. They are not, a DOC sign tells us, built for walkers’ comfort, but to protect the burrows of endangered black petrels. These largish (they grow to be 46 centimetres long) black birds spend most of their life far out at sea and only come to shore to nest. And the biggest colony of these birds is on this mountain top.

Yay, we do it! A hard two-hour hike, mostly upwards, but as the girls (aged 10 and 13) say, the view is awesome. From the top we see forever: to the Poor Knight’s Islands in the north; Kawau and Tiritiri Matangi islands to the east; Waiheke is a shadow in the distance, as are the Mercury Island’s in the south. Hauturu (Little Barrier) has a collar of wispy cloud and the frilled, convoluted skirts of Great Barrier spread below us with dark bush fingers separating curved sandy beaches. The full circle is surrounded by Pacific-blue sea.

When we return to Tryphena later in the morning, the birds have disappeared and a market is in full flight. The shops and cafe are busy and at 11 stalls, locals sell their wares. A nurseryman has a good range of flowering plants and fruit trees, a lady sells jewellery she makes from beads bought at exotic markets when she travels the world in winter, there is a range of hippy-style clothes (this is no place for power-dressing), a locally made range of natural skincare products and honey.

We buy a raffle ticket for a return trip to the island (one can never get enough of this place) and one of Janene’s Ice Dreams.

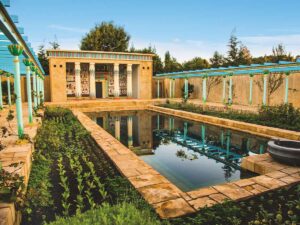

Walking to Kaitoke Hot Springs is a must-do activity, too. The path, a half-hour walk, crosses Kaitoke Swamp on a board walk then follows the edge of a nikau-clad valley to a bush-shaded stream with numerous hot springs. We lower ourselves into incredibly hot water, taking care not to slip on slightly slimy rocks, and then, when we have sweated as much as we can bear, we decamp 20 metres down to where a regular cool stream joins the hot one and relax in warm water. Then we go back to the hot one.

Ah, life is good.